Is the bay clean enough to support commercial shellfish farming?

Bacteria (Fecal Coliform) Status in Morro Bay Shellfish Growing Areas

The waters of the Morro Bay estuary provide not only recreational opportunities and majestic views but also serve as a source of locally-grown food. The bay supports two commercial oyster farms, Morro Bay Oyster Company and Grassy Bar Oyster Company, whose products are sold in markets and restaurants locally and beyond. This industry depends on clean waters in the bay. Regular testing and oversight by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) help ensure that shellfish are safe to eat.

A thriving aquaculture industry puts Morro Bay’s name on the culinary map, as oysters grown in the bay are known for their unique flavor. The future of the industry depends on a reliable supply, and this is only possible if the bay’s waters are clean. A trend in water quality is difficult to determine due to changes in how the oyster growing waters are managed, but the end result of these management changes is that oyster farming can continue in Morro Bay.

Video Presentation: Shellfish Farming in the Morro Bay Estuary

More than 5,000 acres of land have been protected in the lands surrounding the Morro Bay estuary. See what tools the Morro Bay National Estuary Program and our partners use to protect, conserve, and restore these rare coastal lands. Video Presentation by the Morro Bay National Estuary Program’s Assistant Director, Ann Kitajima.

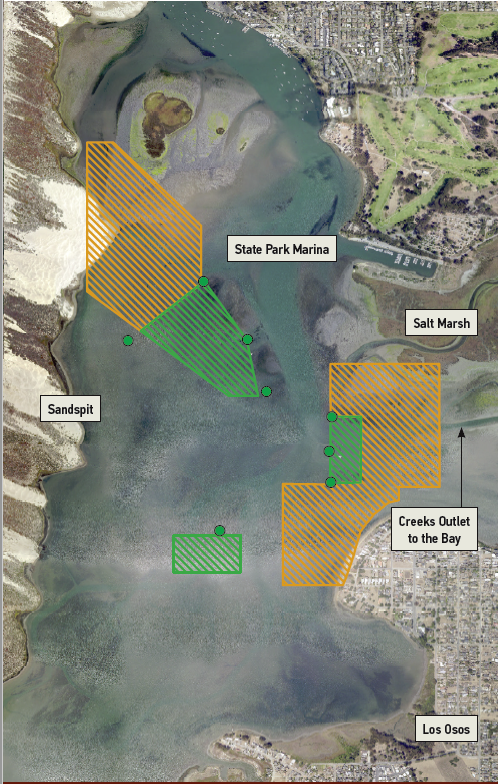

The map above illustrates the lease areas where shellfish can potentially be grown. The green hashed areas show locations where water quality is clean enough for harvesting. These areas have shifted slightly due to changes in water quality conditions and changes in management, but the harvesting acreage has remained relatively stable. The orange hashed areas show sections that either have a history of poor water quality or a lack of data to assess conditions.

Shellfish Lease Areas and Bacteria (Fecal Coliform) Status

Changes in Growing Area Management

To help manage the oyster leases, CDPH added a seasonal closure for the farms, meaning that the farms automatically close during certain times of year when water quality has historically been poor. CDPH also changed the way it implements rainfall closures. Rather than closing when a certain amount of rain falls during a 24-hour period, a closure is triggered when the water levels in Chorro Creek exceed a certain height. High flows in this creek cause concern since bacteria are transported from the creeks into the bay during storm events.

To stay in operation during these closures, Morro Bay Oyster Company designed and built a depuration facility along the Embarcadero. By purifying bay water and using it in onshore oyster cultivation tanks, this facility ensures that oysters are safe to eat, no matter the weather; this allows oyster harvesting to continue on shore even when bay water quality is too low.

The History of the Oyster in Morro Bay

The oyster industry in California began with the Gold Rush. This influx of easterners wanted familiar foods, including the eastern oyster. Native oysters, with their darker meat and strong coppery flavor, did not appeal to eastern palates. Initially, oysters were shipped to California by boat from Washington state. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, fresh eastern oysters could reach the west coast in three weeks. Oyster seed was also sent west, where it was raised to harvestable size, often in San Francisco Bay.

In 1910, the industry began declining in San Francisco, likely due to increasing industrial pollution and changing economics. In 1930, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife introduced the Pacific oyster from Japan. Pacific oysters far outcompeted both the native Olympia oyster and the eastern oyster due to their lower production costs and mortality rates.

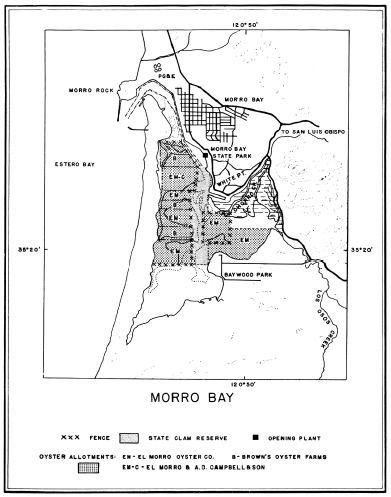

By 1935, over 70% of the 2,300-acre Morro Bay was allotted for oyster growing (shaded dark gray on the historic map). Farmers scattered seed oysters from boats at high tide and harvested them by hand at low tide after about two years.

When trade with Japan was cut off during WWII, Morro Bay obtained seed from Washington state and became the leading oyster producing area in California. In 1964, Morro Bay’s production peaked at nearly 250,000 pounds of shucked oysters harvested during the year.

The Life of an Oyster

In order for the Pacific oysters to spawn, the bay waters must be warm. Because these temperatures are rarely achieved in Morro Bay, oyster farmers must rely on seed from hatcheries for each crop of oysters. Seed for Morro Bay’s farms typically comes from Washington or Hawaii.

Rather than scattering the oysters on the bay bottom, seed are grown in tanks to a size large enough to be put into mesh bags. These bags are put into the bay in the lease areas designated for shellfish farming.

These oysters are known for their ability to grow and thrive in various environments. Their ideal temperature range is 8 to 22 degrees Celsius (46.4 to 71.6 degrees Fahrenheit), but they can tolerate even higher temperatures. Similarly, they can tolerate a wide range of salinities. Their ideal range is 24 to 28 parts per thousand, but they can tolerate salinities as low as 5 parts per thousand.

Oysters help our bay

Oysters are natural filters of ocean water. One oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water, removing pollutants found in the water. However, if the water is too polluted it can affect the development of the oyster, and it can be unsafe for humans to consume them.

What shellfish are native in Morro Bay?

Olympia Oysters

The Olympia oyster is the only oyster native to Morro Bay. When Pacific oysters were introduced to the bay for farming, they outcompeted the Olympia oyster, making it more difficult to find them in the wild. This is the only native oyster on the west coast but the population has been greatly diminished by pollution and over-harvesting.

Olympia Oysters are found in bays and estuaries and they can be found from Southern Alaska to Baja California. Their lifespan is thought to be about 10 years. They can live in waters that are up to 71 meters (233 feet) deep and with a temperature range of 6 to 20 degrees Celsius (42.8 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit). Even though these oysters prefer a salinity level of about 25 parts per thousand, they can survive in lower salinities although in those conditions they have less resistance to parasites.

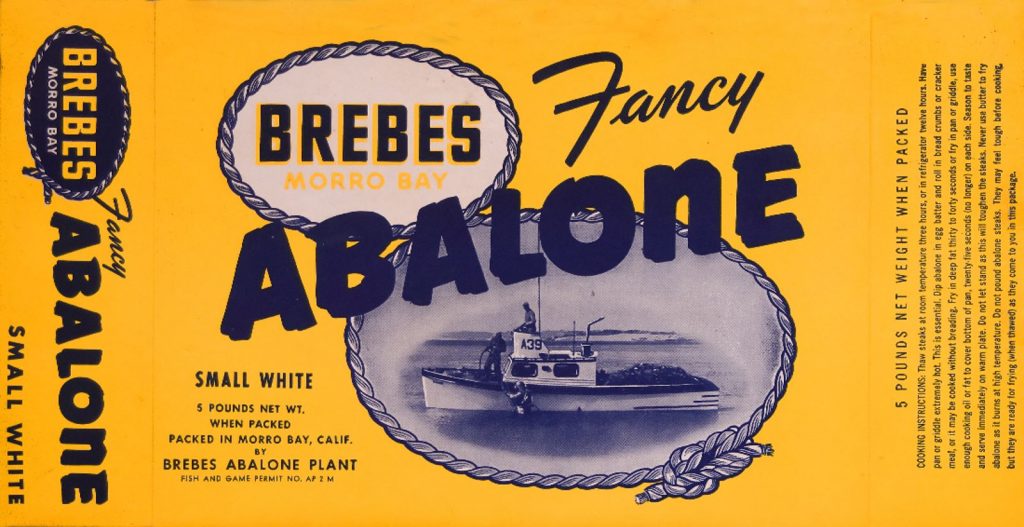

Abalone

Abalone is also native to the area. White, black, red, and green abalone are all found throughout the coast of California and Mexico. Their main food source is algae, but they also eat kelp. They can be found in the intertidal zone to about a depth of 180 meters (590 feet) but usually prefer depth of 6 to 40 meters (20 to 131 feet). Abalone reproduces the same way as oysters do, through broadcast spawning that launches eggs and sperm into the water. After fertilizing takes place, the newly formed abalone larvae will float around for about a week and then go through metamorphosis. After the change, the abalone loses its ability to swim and begins the process toward adulthood. It takes about five to seven years for abalone to reach sexual maturity, and they can be no further than 1.5 meters (5 feet) from each other reproduce successfully. They have a lifespan of 40 to 50 years.

Decline of Abalone

Abalone was at one time plentiful in Morro Bay, but over-harvesting has greatly diminished wild abalone. For more on the history of abalone in Morro Bay check this link out. Fewer abalone has made it harder for abalone to reproduce, in particular because of the length of time it takes for abalone to sexually mature.

Currently, it is illegal to commercially dive and fish for abalone. They can only be obtained through recreational diving or abalone farms.

How might a changing climate affect shellfish?

With the rising acidification and warmer temperatures of our ocean waters, many marine creatures are being affected and our shellfish are no exception. Currently, there is a rising amount of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere and our oceans are absorbing much of it. This in turn lowers the pH of the water, meaning it becomes more acidic. This makes it harder for shellfish to create their calcium-based shells and impacts their survival.

Rising ocean temperatures could potentially affect shellfish spawning time, increase the spread of disease, and decrease the amount of oxygen in the water.

Data Notes

Data and updates to the lease areas in the map were provided by CDPH.

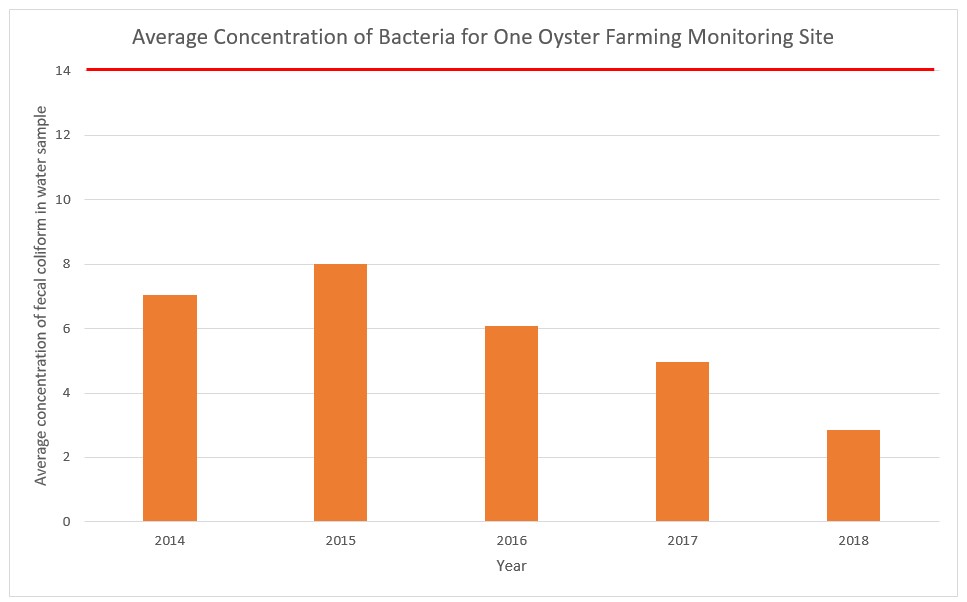

The bacteria data from 2014 through 2018 was analyzed for the geomean of the fecal coliform concentration with data provided by CDPH.

The historical map and information on farming is from a 1963 report by CDFW.