Do the estuary and watershed support a healthy population of steelhead?

Morro Bay and its watershed are fortunate to be a home to a unique species, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Some of these fish spend their entire lives in freshwater creeks and are called rainbow trout. Others—though they are genetically identical—hatch in freshwater creeks, migrate to the ocean to grow to adulthood, and then return to our creeks to reproduce. These fish are called steelhead trout, and they are the anadromous (or saltwater-going) form of the same species. Both varieties of the fish can be referred to generally as trout.

As adults, steelhead and rainbow trout live in different habitats and are different in appearance, despite being genetically identical. The color and patterns on rainbow trout varies slightly depending on habitat, but they can have blue, green or yellow hues with a silvery belly, a pink stripe along their sides and dark spots on their backs. Steelhead are typically larger than rainbow trout and are more silver or brassy in color. For more information on these species, visit the National Wildlife Federation and the NOAA Fisheries websites.

While steelhead were once abundant in our area, they are now federally-listed as a threatened species. These fish require good habitat, clean waters, and creeks free of structures that block their path upstream to spawn and downstream to reach the ocean. Another threat comes in the form of invasive species. Sacramento pikeminnow are known predators of trout and compete with them for food and habitat. The Estuary Program works to maintain water quality and quantity, remove migration barriers, and manage threats to trout, such as this invasive fish.

Sacramento pikeminnow are not native to the Morro Bay watershed, but they are native to parts of California. Pikeminnow prefer streams that have complex habitat such as deep pools and undercut banks that provide shelter. Though considered a slow growing fish, pikeminnow grow rapidly for the first five years of life. They can live for more than 16 years and spawn annually. To learn more about pikeminnow, visit the UC Davis California Fish Website.

Video Presentation: Steelhead Trout in the Morro Bay Area

See how steelhead are doing in the Morro Bay area and learn what the Morro Bay National Estuary Program, Stillwater Sciences, and other partners are doing to support this sensitive species. Video presentation by the Morro Bay National Estuary Program’s Assistant Director, Ann Kitajima.

Using the Latest Science

To better understand the distribution of trout and pikeminnow within Morro Bay’s creeks, we employed a tool called environmental DNA (eDNA). In 2018, researchers took water samples from local creeks and analyzed them for the unique DNA left behind by trout and pikeminnow. Sampling and analysis were conducted on all of the watershed creeks by Stillwater Sciences and the UC Santa Barbara Marine Sciences Institute.

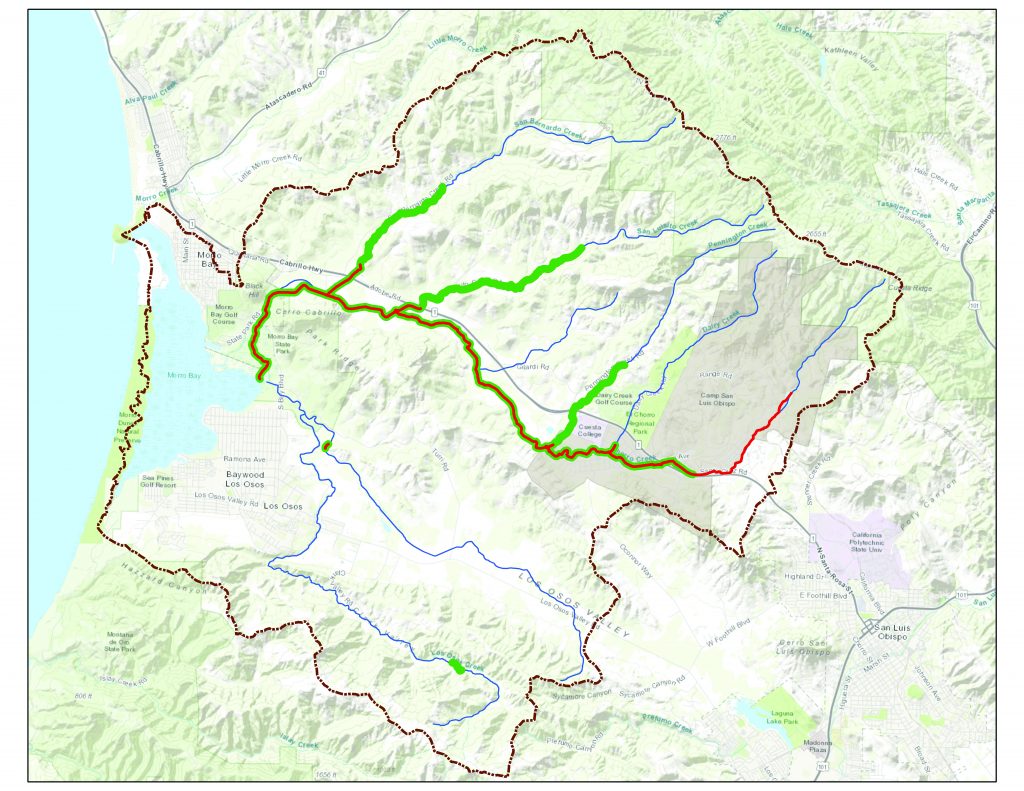

Trout and Pikeminnow Distribution in the Morro Bay Watershed

The results of the eDNA sampling and observations from snorkel surveys conducted in 2019 by the California Conservation Corps confirmed the presence of trout and pikeminnow throughout Chorro Creek, with limited distribution in tributaries to Chorro Creek. In San Bernardo, San Luisito, and Pennington Creeks, trout were detected or observed both downstream and upstream of partial barriers at Highway 1, while pikeminnow were limited to the lowermost portions of tributaries. An exception was San Bernardo Creek where pikeminnow DNA was detected upstream of the partial barrier at Highway 1. Trout and pikeminnow DNA were also detected in the lower section of Warden Creek. Although no DNA from either species was detected in lower Los Osos Creek, trout were observed in upper Los Osos Creek near Clark Valley Road during snorkel surveys in 2019.

Impact of Invasive Pikeminnow on Trout

After eDNA analysis alerted us to the presence of both species in local creeks, the next step was to assess the level of pikeminnow predation on trout in Chorro Creek. To do this, scientists analyzed the stomach content of pikeminnow for eDNA to determine if they were consuming trout. Out of nearly 40 pikeminnow sampled, about 20 percent had trout DNA in their stomachs. If each of the large, predatory adult pikeminnow consumes around 40 juvenile trout per year and if the entire population of around 200 large pikeminnow in Chorro Creek has a similar predation rate, the estimated annual loss would be more than 7,000 juvenile trout per year.

Invasive Species Management

Since pikeminnow predation on trout is so high, the Estuary Program worked with biologists from Stillwater Sciences to reduce the pikeminnow population. For a fish that is a voracious predator for around three to four years of its life, removing one pikeminnow can protect around 150 to 200 trout juveniles.

Pikeminnow are thought to have been initially introduced to the Chorro Reservoir (located above the California Men’s Colony) and are now found throughout Chorro Creek.

The Estuary Program and partners have identified ways to control pikeminnow in the watershed, including removing pikeminnow from Chorro Creek and Chorro Reservoir to improve the chances of steelhead survival. In the summer of 2017, the Estuary Program, Stillwater Sciences, California Conservation Corps, and volunteers completed fish surveys to remove pikeminnow and identify areas that had an abundance of native fish. Surveyors observed many species of native fish including trout, speckled dace, Sacramento sucker, and three-spine stickleback. The survey provided baseline data to track fish populations over time. Similar surveys were completed in September of 2018, using an electrofishing backpack. This backpack stuns the fish so that they can be captured and identified. Native species were returned unharmed to the creek, and captured pikeminnow were removed.

How do you assess the steelhead population?

Snorkel surveys are one method commonly used for estimating fish populations. Divers swim through the water and count all the target species, such as steelhead and pikeminnow, that they can see. Good results depend on good water visibility and surveyors that can quickly identify fish species. These surveys are commonly conducted in the summer through early fall, when stream flows are relatively low and water clarity is high.

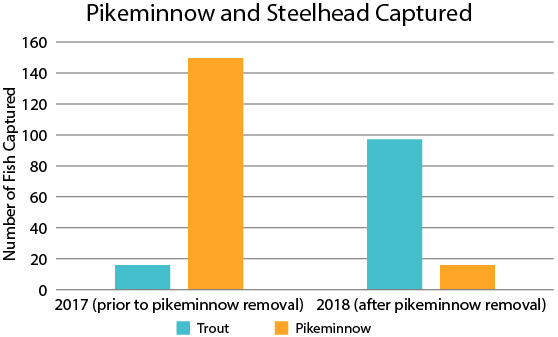

Impacts of Pikeminnow Management

Prior to pikeminnow removal efforts in 2017, a section of Chorro Creek had very high numbers of pikeminnow (the orange bars on the graph) with very few trout (the blue bars on the graph). In 2018, the same locations had high numbers of trout and only a few pikeminnow. Although the data is limited, pikeminnow removal appears to greatly benefit trout.

Removing Barriers to Migration

Since steelhead spend portions of their life in creeks such as ours and a portion in the ocean, the ability to move freely between these two environments is crucial. Structures in the waterways, whether human made or naturally-occurring, can block free movement of fish.

Data Notes

Stillwater Sciences and UC Santa Barbara Marine Sciences Institute conducted the sample collection of creek water and pikeminnow gut content for eDNA analysis. The map indicating pikeminnow and trout presence was developed by Stillwater Sciences based on the eDNA results and snorkel surveys conducted in 2019. Estimations of pikeminnow predation rates on trout were developed by Stillwater based on eDNA results and their extensive experience working on Chorro Creek.

Snorkel survey information: https://www.wildsteelheaders.org/steelhead-101-using-snorkel-surveys-to-estimate-adult-steelhead-escapement/

Sacramento pikeminnow information: http://calfish.ucdavis.edu/species/?uid=82&ds=241

Rainbow trout and steelhead information: https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Fish/Rainbow-Trout-Steelhead

Steelhead information: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/water_issues/programs/hearings/cachuma/comments_rdeir/edc/boughton_etal2006.pdf