Are bird populations that depend on the bay and surrounding lands stable?

Birds are a useful proxy for the health of an estuary. If there are many different types of birds and their populations are stable, that is a sign that the bay is faring well.

More than 200 types of birds are seen around Morro Bay in the wintertime. This number has been stable for the past two decades, indicating good local conditions for a wide variety of birds to thrive. However, some types of birds are facing conditions that make it hard to survive in our area.

Video Presentation: The Health of Local Bird Populations

Video presentation by the Morro Bay National Estuary Program’s Assistant Director, Ann Kitajima.

Protecting Plovers

The western snowy plover, considered threatened under federal law, prefers to nest on the same sandy beaches frequented by human visitors. These small, black, brown, and white birds resemble animated cotton balls with legs, darting between dunes to seek food. They lay their eggs directly in the sand, making them vulnerable to being stepped on or eaten by predators. Plovers can also abandon their nests if they are disturbed too often.

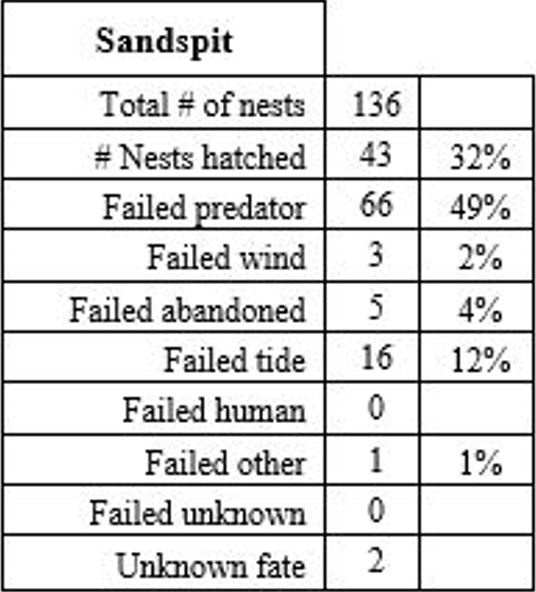

The Morro Bay sandspit is an important nesting site in coastal California. California State Parks manages this area to support the recovery of these threatened birds. In 2018, only 169 nests were laid compared to an average of 234 nests over the previous four years. Though the overall number was low, 53% of the nests hatched, which was a five-year high. Of the 47% that failed, most suffered from abandonment or animals such as red fox and coyote eating the eggs. Despite the dip in the number of nests laid in 2018, the general trend has been increasing since 2008.

The San Luis Obispo Coast District of California State Parks monitors 45 miles of coastline in San Luis Obispo County for Western Snowy Plover. Efforts include monitoring of population counts, adult plover behavior, nests, predator and human activity, and chicks and fledglings.

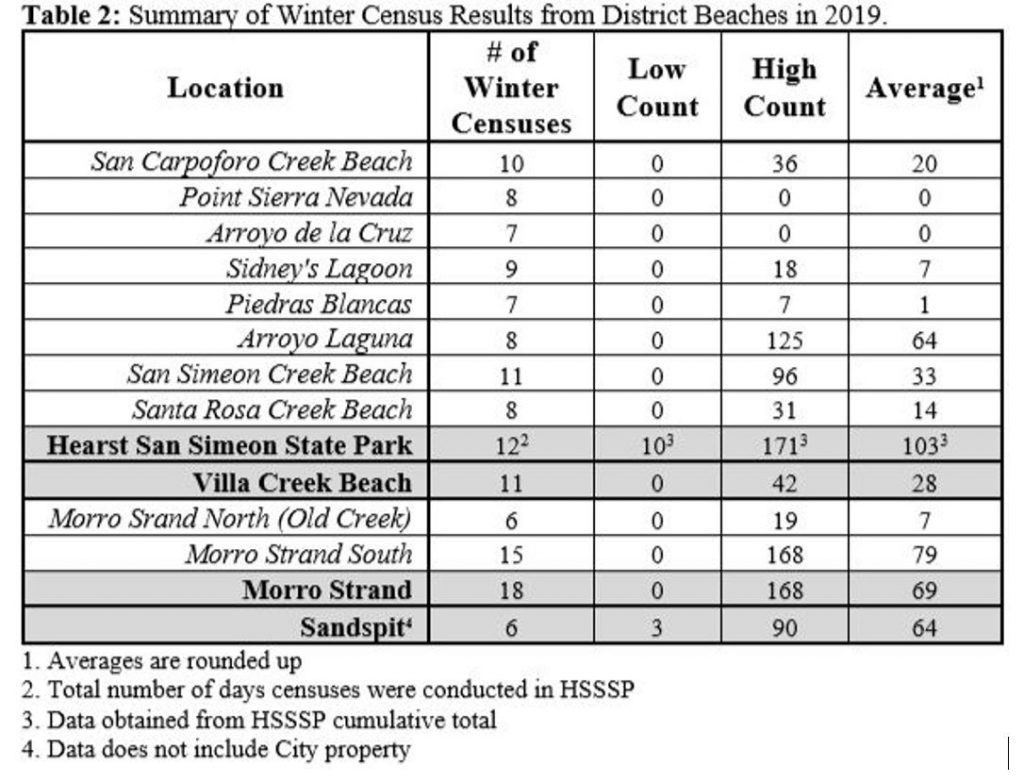

For the 2019 monitoring season, State Parks conducted counts from October 2018 to February 2019. Our District beaches have historically been utilized by plover as wintering grounds, rather than in the breeding season. Our area has seen a general increase in Corvid (including ravens) presence on most beaches. To stop Corvids from preying on the nests, staff constructed mini enclosures. While the Sandspit was the only beach in the District to meet recovery standards in 2019, it still had the lowest number of breeding adults within the past 14 years. High tides and a narrow beach were other factors that may have impacted the low numbers. Morro Strand State Beach had its most productive nesting year recorded without using nest enclosures, as predators did not find the nests until the end of the season.

During the May survey, a minimum of 77 adult plovers were observed. District beaches had a hatch rate of 33% in 2019, down from the average rate of 48% (2005-2018). 44% of nest failures are due to predators.

The following table shows the population count from county beaches during 2019.

What is the Pacific Flyway?

Morro Bay is one stop on the long journey more than a billion birds travel each winter from as far north as Alaska to the warm climates of Baja California and Central and South America. The flyway is over 4,000 miles long and up to 1,000 miles wide. While it is unknown exactly how birds navigate these long journeys, it is thought to be a combination of using the position of the sun and stars and through sensing the earth’s magnetic field. They also navigate via visual landmarks such as the coastline. Regardless of how they navigate, birds rely on areas like Morro Bay to provide clean water, food, and safe resting places along the way. To learn more about the Aubudon’s Pacific Flyway Priority Birds, visit their website.

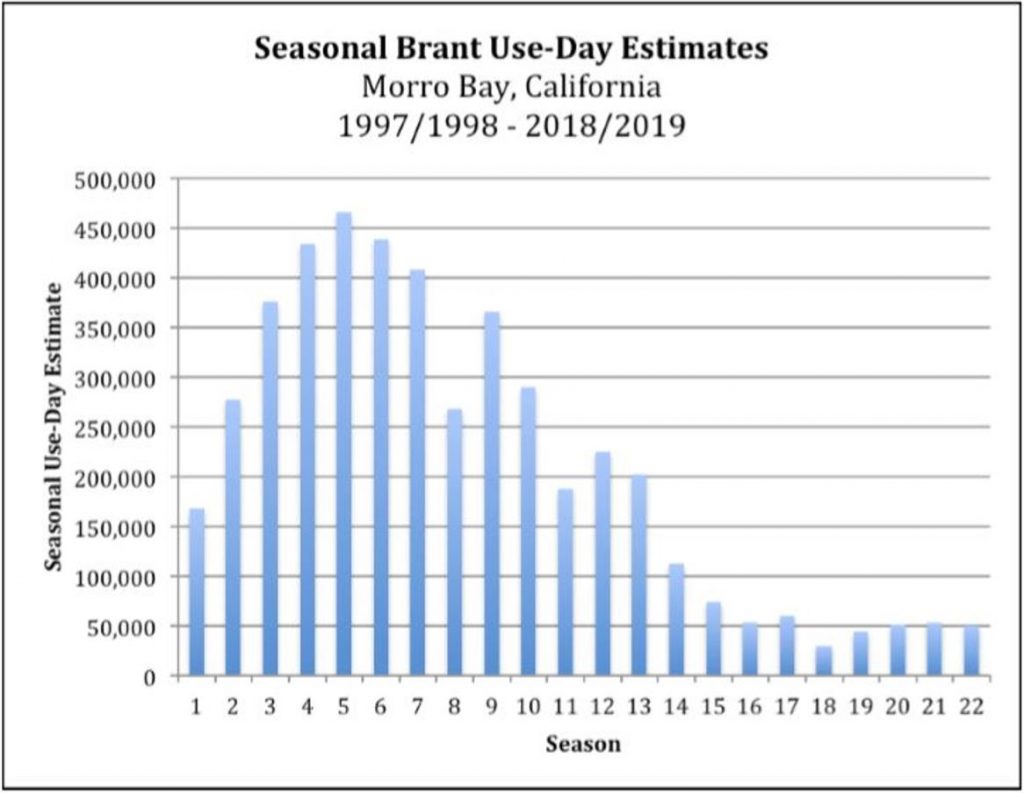

Less Eelgrass Means Fewer Brant

Huge flocks of black brant were once common on the bay in wintertime, when they stopped here to rest and snack on eelgrass during their long migration from Alaska to Baja California. With the decline of eelgrass in Morro Bay and warmer winters in Alaska, fewer brant of the next generation are learning to stop here. Healthy eelgrass beds in Morro Bay can offset changes elsewhere along the coast only if each new generation learns to locate Morro Bay as a place of refuge.

Local brant data is collected by John Roser, a retired biologist who has long had an interest in these unique birds. The survey method includes six counts of Brant conducted each year between November and April. The brant use for the month is estimated by this single mid-month survey.

Although no use-day data for Morro Bay exists prior to the 1997/1998 season, some historical data is available to provide context.

| Time Period | Average Count | High Count |

| 1931 to 1942 | 6,800 | 11,100 |

| 1950 to 1966 | 6,000 | 11,800 |

| 1998 to 2019 | 1,430 | 4,600 |

To read more about this work, check out this blog post by Roser.

Morro Bay Shorebird Data

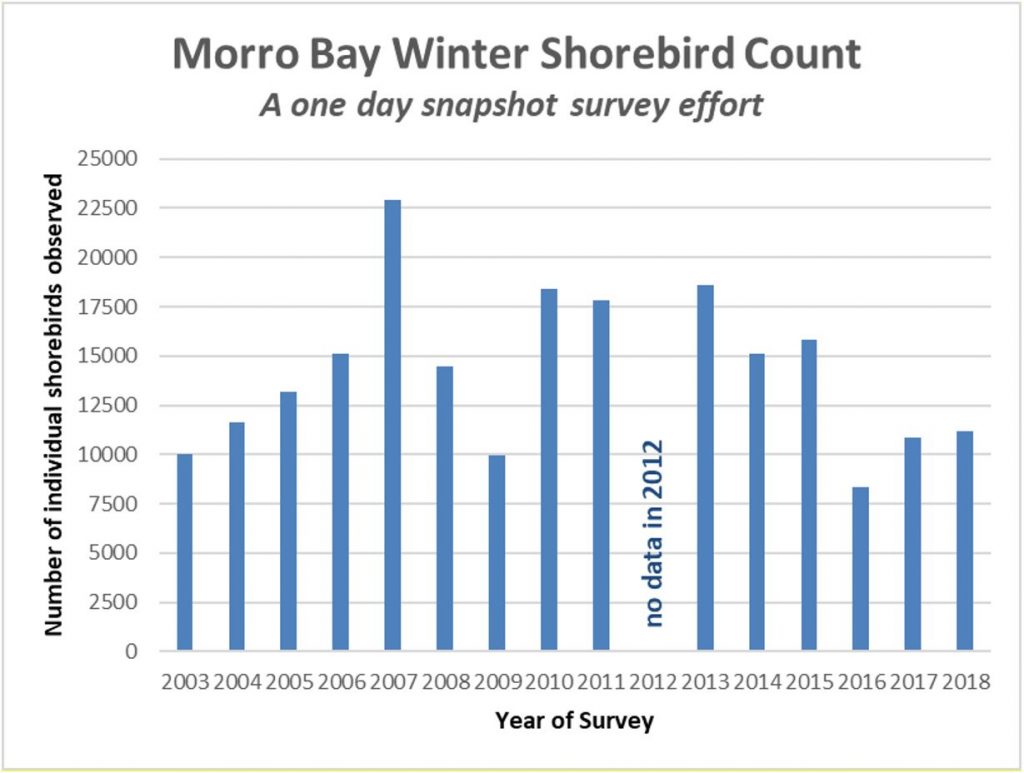

A fall shorebird count in Morro Bay is a part of an effort to track trends of wintering shorebirds along the Pacific Flyway. Point Blue Conservation Science leads a program called the Pacific Flyway Shorebird Survey. The data feeds into the Migratory Shorebird Project, which surveys wintering shorebirds on the Pacific Coast of the Americas in 13 countries. For more information on the effort and to see data from Morro Bay and beyond, visit the PRBO data portal.

Climate Change Impacts on Birds

Audubon has ongoing efforts to better understand how our changing climate might impact birds. In their 2019 report Survival by Degrees: 389 Bird Species on the Brink, they analyze the vulnerability of birds across North America. Almost two-thirds of America’s birds are vulnerable to climate change, and in North America, 37% of birds are at a high risk of extinction. Birds typically respond to climate change by shifting their ranges, but the current relatively rapid rate of change leaves birds vulnerable. A goal of the report is to determine how different climate change scenarios impact habitats and species. Slowing climate change to reduce warming could reduce the vulnerability of many species of birds. To learn more, you can find the full report on Audubon’s website.

Regional Bird Populations

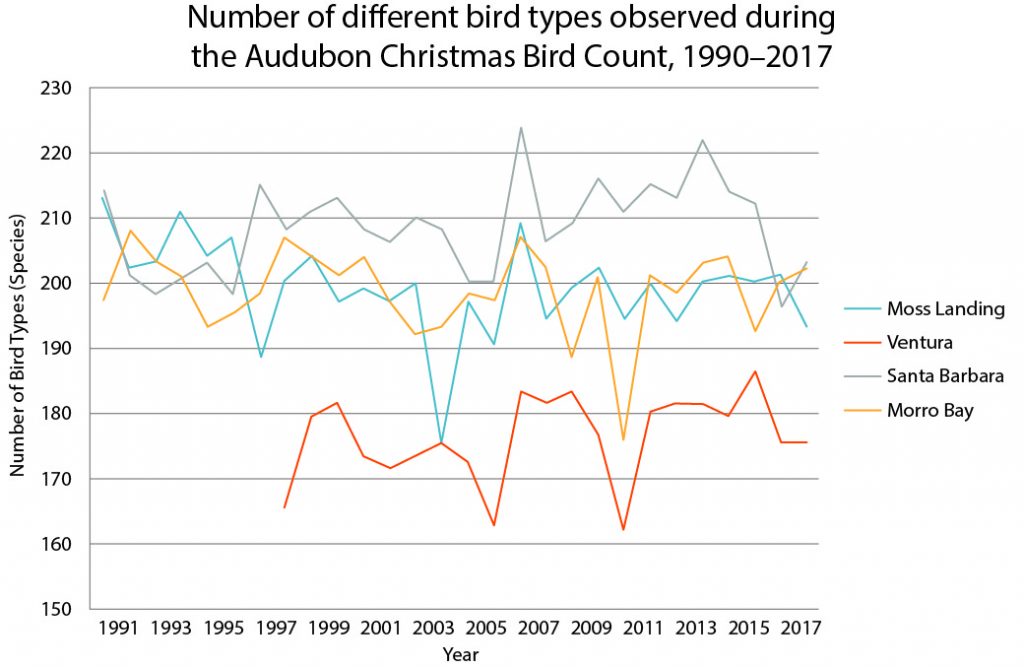

Each December, the National Audubon Society hosts a Christmas Bird Count event where birders across the nation gather to count birds in their local area. The effort is known as the longest-running citizen science bird project.

Locally, the count is organized by Morro Coast Audubon Society. The 2019 Morro Bay Christmas Bird Count was held on Saturday, December 14 and was conducted within a 15-mile diameter circle centered on the intersection of Turri Road and Los Osos Valley Road. The area was divided into 54 sectors. The count recorded 197 species, which is two species less than the average count for data going back to 1980. A total of 38,991 birds were counted, which is nearly 20% less than the average of counts since 1980. Since the surveys began in 1948, the total number of unique species counted is 319. A summary of the 2019 survey is available on the MCAS website. For full details on the survey and to see trends in the data from our area and beyond, visit the Audubon Christmas Bird Count website.

Data Notes

The Regional Bird Population data was from the Audubon Christmas Bird Count: https://www.morrocoastaudubon.org/p/mcas-christmas-bird-count.html and https://www.morrocoastaudubon.org/2020/01/2019-morro-bay-cbc-final-results-are-in.html

The Morro Bay Shorebird Population data is from a Morro Coast Audubon Society-led one-day shorebird survey, which takes place each fall using Point Blue survey methods: https://data.prbo.org/apps/pfss/

Western snowy plover data is collected and analyzed by San Luis Obispo Coast District of California State Parks, as part of recovery efforts for this federally threatened species. For more information on Western Snowy Plovers: https://www.fws.gov/arcata/es/birds/WSP/plover.html

Local brant data is collected by John Roser, local biologist and citizen scientist, using standardized methods. The information came from his report titled Brant Counts for Morro Bay, California 2018 – 2019 Season.

Information about brant migration patterns is based on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data.

Pacific Flyway information: https://openspacetrust.org/blog/pacific-flyway/

Audubon’s report on climate change impacts on birds: https://www.audubon.org/sites/default/files/climatereport-2019-english-lowres.pdf