Is the bay clean enough to support commercial shellfish farming?

Yes, in active harvesting areas.

Shellfish Farming in Morro Bay

How to Read Estuary Health Symbols

The Estuary Health Symbols represent how the status of each question is changing over time. A round symbol indicates that the trend is stable. An arrow indicates an improving trend (up arrow) or a worsening trend (down arrow). The color of the base of the arrow indicates the status of historical data and the color of the triangular part of the arrow indicates the status of the newer data. The color of the symbol indicates the status as follows: Good/Very Good (green), Fair (yellow), Poor (orange), Very Poor (red), and Unknown (grey).

This symbol indicates that the water quality was Very Poor and has improved to Poor.

This symbol indicates that the trend is stable but we lack adequate data to assign a status.

Very Good/Good

Fair

Poor

Very Poor

Unknown

Indicator symbol: Very Good/Good

Hover symbol for indicator information

Morro Bay is fortunate to be one of the few areas on the California coast with our own source of local oysters. The Morro Bay Oyster Company and Grassy Bar Oyster Company grow Pacific oysters in the bay’s waters for sale in markets and restaurants. There are approximately 73 acres available for oyster farming, which is only 3% of the bay’s total acreage. The aquaculture industry depends on clean water, and the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) is responsible for determining if the water quality in the bay is suitable for growing oysters. One of the measures they consider are the levels of bacteria in the water at the oyster farming sites.

Header photo courtesy of Grassy Bar Oyster Company.

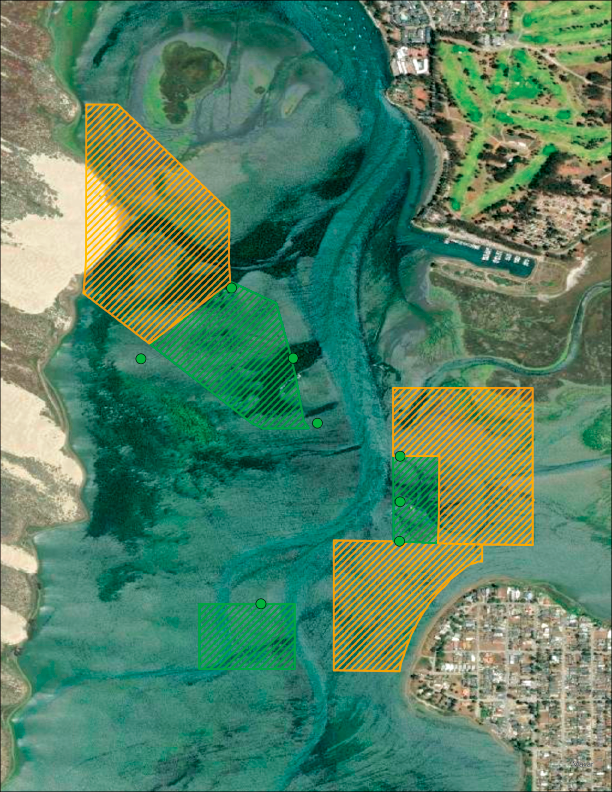

Bacteria (Fecal Coliform) Status in Morro Bay Shellfish Growing Areas

Morro Bay Shellfish Growing Areas

The shaded areas on the map represent potential shellfish farming lease areas. The green sections of each lease area have clean water where shellfish harvesting is permitted. Shellfish harvesting is not permitted in the orange areas either because of poor water quality or a lack of data.

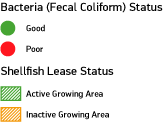

A Closer Look at Water Quality

The oyster farms in Morro Bay are required to conduct regular water quality testing to ensure the shellfish are not exposed to high concentrations of pathogens or biotoxins. Samples are collected monthly and after rainfall events, since runoff is known to bring bacteria and other pathogens with it when draining into the bay. The farms are required to close seasonally for most of the winter, when rainfall is typically the highest. After a storm has passed, the water quality samples must meet all regulatory requirements before the farms can reopen.

Each year, CDPH compiles the results from water quality sampling into an Annual Sanitary Survey Update Report for the shellfish growing areas. These reports are used to reevaluate pollution sources and management practices to ensure the oysters are safe to bring to market. In the most recent report, covering the 2021-2022 season, no biotoxin concentrations were reported above closure limits and seasonal closures have proven effective at keeping bacteria concentrations below exceedance thresholds. In addition, there were no bacteria concentration violations from the local wastewater treatment plants and there were no reports of illicit discharge from vessels docked in the bay.

Updates from the Farms

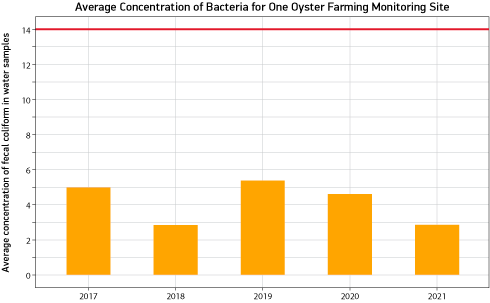

History of Oyster Farming in Morro Bay

The oyster industry in California began with the Gold Rush. This influx of easterners wanted familiar foods, including the eastern oyster. Native oysters, with their darker meat and strong coppery flavor, did not appeal to eastern palettes. Initially oysters were shipped to California by boat from Washington state. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, fresh eastern oysters could reach the west coast in three weeks. Oyster seed was also sent west, where it was raised to harvestable size, often in San Francisco Bay.

In 1910, the industry began declining in San Francisco, likely due to increasing industrial pollution and changing economics. In 1930, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife introduced the Pacific oyster from Japan. Pacific oysters far out-competed both the native Olympia oyster and the eastern oyster due to their lower production costs and mortality rates.

This historical map from a California Department of Fish & Wildlife report shows the areas available for oyster farming and clamming in the 1930s. By the mid-1930s, 1,677 acres of the 2,300-acre bay were allotted for oyster farming, making it the top oyster-producing area in the state. Farmers scattered seed oysters from boats when the beds were underwater and harvested them by hand at low tide after about two years of growth.

When trade with Japan was cut off during World War II, Morro Bay obtained seed from Washington state and became the leading oyster producing area in California. In 1964, Morro Bay’s production peaked at nearly 250,000 pounds of oysters harvested during the year. At that time, oysters were sold shucked in jars. Today, consumers prefer their oysters whole in the shell. There are currently 75 acres available for oyster farming, which is only 3% of the bay’s acreage.

Monitoring Partnerships

Olympia Oysters: Morro Bay's Only Native Oyster

The Olympia oyster is the only oyster native to the Pacific coast of North America, including Morro Bay. They are a keystone species in the intertidal zone due to their ability to improve water quality and provide important habitat for other species. Oyster filter feeding reduces the risk of harmful algal blooms and improves water clarity, allowing more light to penetrate through the water, which benefits marine plants like eelgrass.

Olympia oysters are found in bays and estuaries from Southern Alaska to Baja California. Their lifespan is thought to be about ten years. They can live in waters that are up to 71 meters (233 feet) deep and within a temperature range of 6 to 20° Celsius (42.8 to 60° Fahrenheit).

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, the Olympia oyster was so abundant in Morro Bay that the Chumash people relied on them as a major food source. Unfortunately, Olympia oysters have been threatened throughout their range by habitat loss, disease, pollution, and overharvesting. The decline began with the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s and has continued to the present day. Olympia oysters and other shellfish are currently impacted by excess carbon emissions that lead to ocean acidification, which can inhibit shell formation.

Cal Poly researchers began a study of Morro Bay Olympia oysters in the summer of 2022 by counting oysters along fifty-meter transects in the intertidal zone during low tides. While a study conducted in 2009 found no Olympia oysters in Morro Bay, the recent Cal Poly survey revealed that they are making a comeback. Cal Poly researchers found 482 Olympia oysters and 393 Olympia oyster scars (spots where oysters had been previously) in the bay.

Just like mature oysters, oyster larvae need to attach to hard substrates like rocks, pilings, piers, or other shells. Cal Poly researchers placed larval recruitment tiles in various sections of the bay and monitored them periodically under a microscope to check for attachment. Five juvenile Olympia oysters were found on the tiles at Tidelands Park, the first recruitment to be observed in two years of monitoring.

These monitoring efforts are useful because they show us which areas are preferred habitat for Olympia oysters as well as when and where they reproduce. This data informs future oyster restoration and habitat protection projects in Morro Bay.

Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring

Data Notes

Lease areas displayed in the map, data from the 2021-2022 Annual Sanitary Survey Update Report, and regulations outlined in the 2022 Management Plan for Commerical Shellfishing in Morro Bay, California were provided by CDPH.

The bacteria data from 2017 through 2021 was analyzed for the geomean of the fecal coliform concentration with data provided by CDPH.

The historical map and information on farming is from a 1963 report by CDFW.