If you’ve spent time in the Morro Bay estuary, you’ve likely noticed changes over the years. One of the most significant changes has happened below the water’s surface from a bay-wide expansion of intertidal eelgrass. Changes to eelgrass habitat not only affect how the bay looks but also shape the aquatic community, since eelgrass provides shelter, nursery habitat, and foraging grounds for many species. The Estuary Program recently completed a study exploring how fish communities have been affected by changes in eelgrass over time. This study builds upon historic data collected at different stages of eelgrass extent, helping us assess how fish communities have responded to shifts in habitat.

Eelgrass Change Over Time

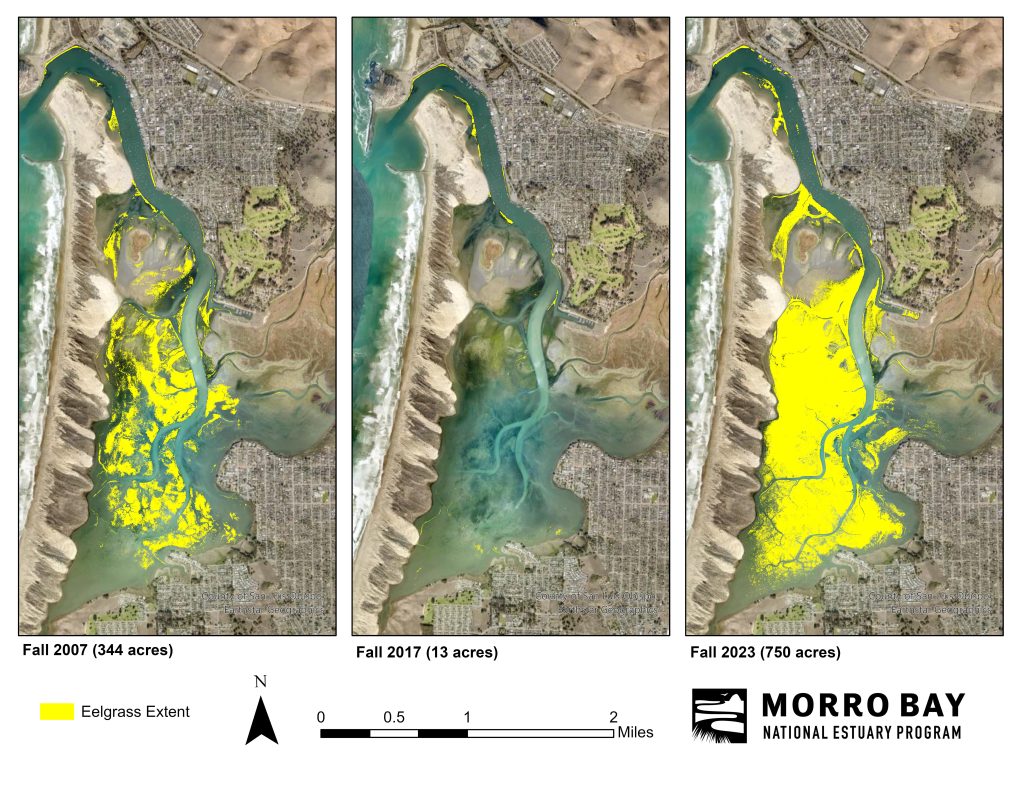

Between 2007 and 2016, Morro Bay lost over 95% of its eelgrass. Signs of eelgrass recovery emerged in 2017, with eelgrass expanding from 13 acres in 2017 to 146 acres in 2020. By 2023, mapping efforts showed a significant increase to 750 acres.

If you’d like to learn more about the history of eelgrass in Morro Bay, please visit https://www.mbnep.org/eelgrass/.

Building Upon Historic Data

With more eelgrass habitat available, we were interested in how the fish community had responded. Would the fish communities resemble those seen before the eelgrass decline? Or had the dramatic loss of habitat caused lasting changes?

To investigate these questions, we looked at two key datasets. The first came from Dr. John Stephens of Occidental College, who piloted a fish monitoring project in Morro Bay in 2006 in partnership with Cal Poly’s San Luis Obispo Science and Ecosystem Alliance. His work documented fish communities in the bay before the start of the eelgrass decline when about 300 acres of eelgrass were present.

In 2016, when only about 13 acres of eelgrass were present, Dr. Jennifer O’Leary of Cal Poly and NOAA Sea Grant repeated Stephens’ work using many of the same monitoring sites and methods. By comparing her results to Stephens’ data, she assessed how fish communities had changed after a significant loss of eelgrass habitat. Her findings showed that while overall fish abundance and biomass remained steady between the two periods, the types of fish had shifted. Habitat generalist species like flatfish became more common, while eelgrass-dependent species like bay pipefish had declined (O’Leary et al., 2021).

These historic datasets provided the foundation for our study design. We used a similar monitoring methods to identify species present in different estuary habitats.

Our Findings

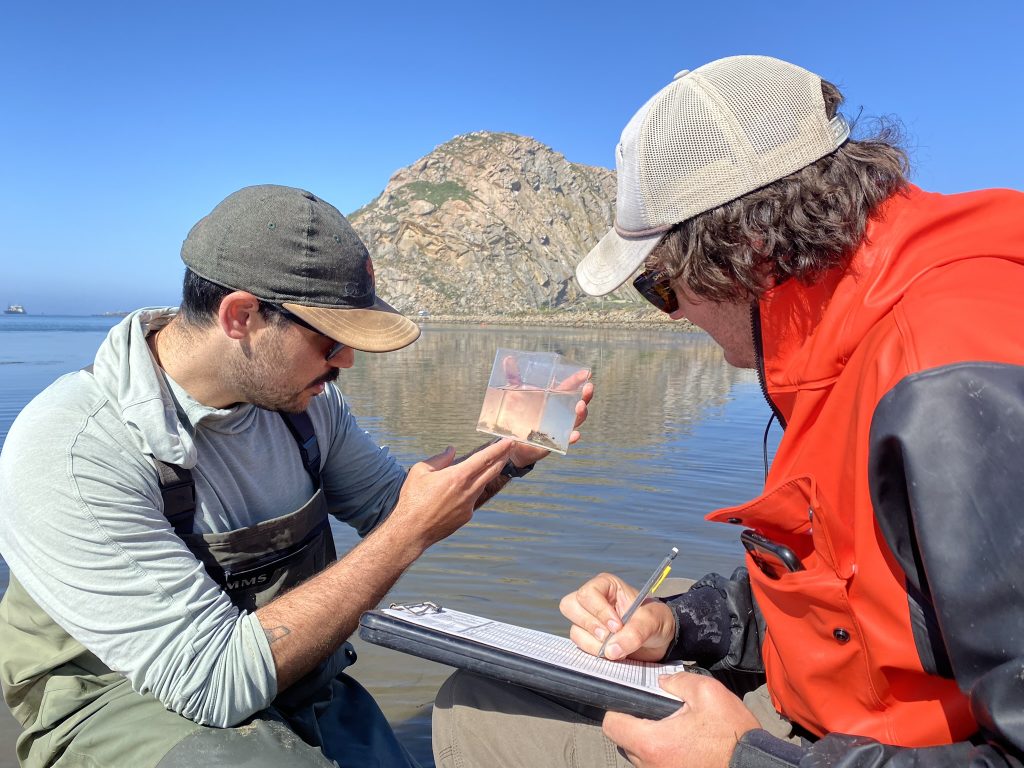

The Estuary Program collected fish data in Morro Bay during fall of 2023 and spring of 2024, a time of eelgrass abundance. A total of 8,317 fish from 24 different taxa were collected over the course of the study. Bay pipefish (Syngnathus leptorhynchus) was the most abundant species captured, accounting for over 40% of the total catch, followed by arrow goby (Clevelandia ios) at 20%, and shiner perch (Cymatogaster aggregata) at 10%.

Shifts in species composition are closely related to changes in eelgrass acreage. During times of eelgrass abundance, habitat specialists like bay pipefish were more prevalent in the bay, whereas during times with minimal acreage, habitat generalists like speckled sanddabs were more common. This continued to be the case for the 2023-2024 monitoring effort, where more eelgrass meant that habitat specialists like bay pipefish dominated the overall catch. These slender-bodied pipefish were most abundant in the dense eelgrass beds of the tidal flats, while habitat generalist species like flatfish were most prevalent in the open channel areas. Shoreline habitats, where eelgrass cover is variable, contained a mix of both specialists and generalists. Overall species richness (the number of different species) was significantly higher in shoreline areas with eelgrass compared to those without.

Some Unexpected Results

While most species persisted across different monitoring periods, a species of flatfish called English sole (Parophrys vetulus) was not captured during the 2023-2024 effort, despite being abundant in previous Morro Bay studies. Additionally, California lizardfish (Synodus lucioceps) was documented in the bay for the first time during the most recent effort. While we do not know the direct cause of the absence of English sole or new appearance of California lizardfish, some potential reasons could include changes in ocean temperatures, shifts in habitat use, or differences in sampling methods. The lack of English sole may also be attributed to a lag in recovery time, as multiple years of minimal eelgrass habitat may have impacted juvenile rearing, affecting their future populations even as eelgrass rebounded.

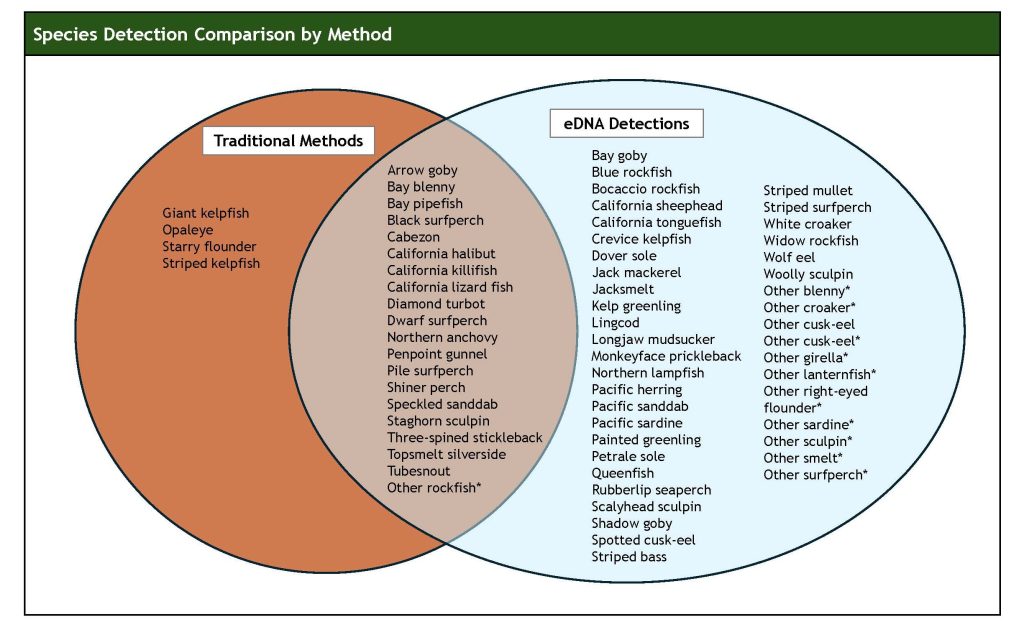

Using eDNA to Monitor Fish

In addition to historic methods, our team added eDNA collection, a new tool to assess fish biodiversity. Staff collected water samples from the areas where fish were captured and sent them to a lab to analyze the DNA left behind by the fish. This technique identified nearly three times as many species as our traditional net methods, giving us a more complete picture of the bay’s complex fish community. Fish DNA was sometimes detected in unexpected habitats possibly due to the moving and mixing of genetic material throughout the bay. There were also some species that were missing from our DNA results, like sharks and rays, which are known to inhabit Morro Bay. Some studies have found that detecting these species with eDNA can be challenging, especially in areas with high biodiversity.

While this work is promising for increasing the ability to identify fish without the more expensive and complex traditional netting methods, there are some limitations to its use. Future efforts may use more targeted DNA techniques to track species of interest like steelhead or tidewater goby.

Our Next Steps

Eelgrass plays a vital role in maintaining a healthy estuarine ecosystem, providing food and shelter for a diverse range of species. When eelgrass in the bay thrives, so do a variety of fish species, especially those who are uniquely adapted to life in seagrass beds. The Estuary Program will continue to map and monitor eelgrass in the bay to support sensitive habitats and aquatic life in Morro Bay’s diverse estuarine environment.

References

O’Leary, J. K., Goodman, M. C., Walter, R. K., Willits, K., Pondella, D. J., & Stephens, J. (2021). Effects of estuary-wide seagrass loss on fish populations. Estuaries and Coasts, 44, 2250–2264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-021-00917-2.

O’Leary, J. K. (Unpublished). Raw data Morro Bay fish sampling (2016-2018).

Stephens, John S., Jr. (2006-2007). [Raw Morro Bay fish data]. Occidental College. Unpublished raw data. Funded by California Polytechnic State University SLO Science and Ecosystem Alliance (SLOSEA). Data ownership transferred to D. J. Pondella, Occidental College.

Stillwater Sciences. (2025). Morro Bay Estuary Fisheries Monitoring. Technical Report. Prepared by Stillwater Sciences, Morro Bay, California for Morro Bay National Estuary Program, Morro Bay, California.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds.

- Subscribe to our seasonal newsletter: Between the Tides!

- We want to hear from you! Please take a few minutes to fill out this short survey about what type of events you’d like to see from the Estuary Program. We appreciate your input!