Who Cares About Rocks?

With lizards darting across the trail and poppies climbing up the hillsides, it is easy to tread over a fundamental element of our natural world: rocks. While they lack the charisma of a red-tailed hawk or a lupine meadow, they offer a wealth of information.

Rocks are the Earth’s history books. Their colors, textures, and shapes provide insight into ancient landscapes like oceans, volcanos, and deserts. Morro Rock is no exception. Everything from its crystalline makeup to its impressive size reveal Morro Bay’s rich history that began almost 30 million years ago.

Texture and Mineralogy of Morro Rock

In a field geology course, it’s common for professors to instruct students to “get your noses on the rock.” While it sounds silly, close examination is the best way to identify how a rock formed without the need for a laboratory or textbook. Let’s nurture our inner geologists and imagine we’re standing at the base of Morro Rock, trying to understand how it formed.

If you picked up a loose piece of rock from the ground, you would notice large white spots on a matte grey background. In the sunlight, some of the white spots appear smooth, while others would glint like glass. You might also catch a glimpse of smaller black crystals as they catch the light. Just by their color and how they shine in the light, geologists can identify that these crystals are white feldspar, clear quartz, and black hornblende.

The spotted appearance tells us Morro Rock has a porphyritic (pronounced por-fuh-rit-ik) geologic texture, which happens when rocks cool quickly, only leaving time for some crystals to fully form. Think of it like a partially blended rock smoothie. Going into the blender are our feldspar, quartz, and hornblende. After a few blitzes, you still have big chunks of the initial ingredients (the crystals you can see with the naked eye). But, you also have a mixture of blended small rock chunks as the base of your smoothie (the matte background).

The crystal types and textures help us to identify Morro Rock as the igneous rock dacite (pronounced day-site). If you look at the other peaks that make up the Nine Sisters, stretching from San Luis Obispo to Morro Bay, you will see that they are also dacites. This indicates they are likely from the same chain of volcanos. But how did volcanos come to be on California’s Central Coast, and where are they now?

Geologic History of the Central Coast

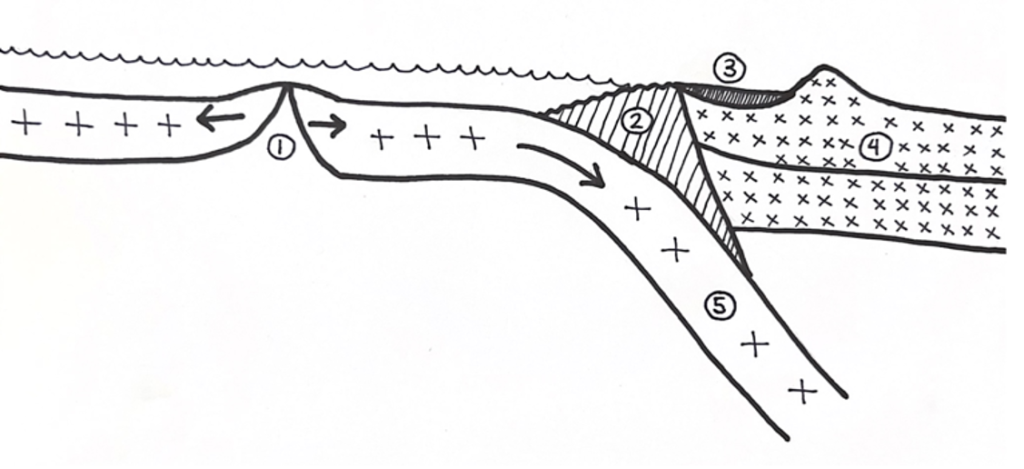

Volcanoes are born from the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates. At mid-ocean ridges (1 on the figure below), magma rises through the ocean floor to create new crust. Along the coasts, tectonic plates are recycled as they dive—or subduct—into the Earth’s mantle, often generating volcanos. Since volcanoes typically form further inland in areas like the Sierra Nevada, why did Morro Rock form along the coast?

Tectonic Plates

About 27 million years ago, a now almost completely disappeared tectonic plate called the Farallon Plate (5 on figure) was subducting off the coast of California, as seen below.

Key: 1= mid ocean ridge, 2= Franciscan Formation, 3= forearc basin, 4 = continental crust, 5 = oceanic crust, 6 = magma plume, 7 = volcano that formed the Nine Sisters.

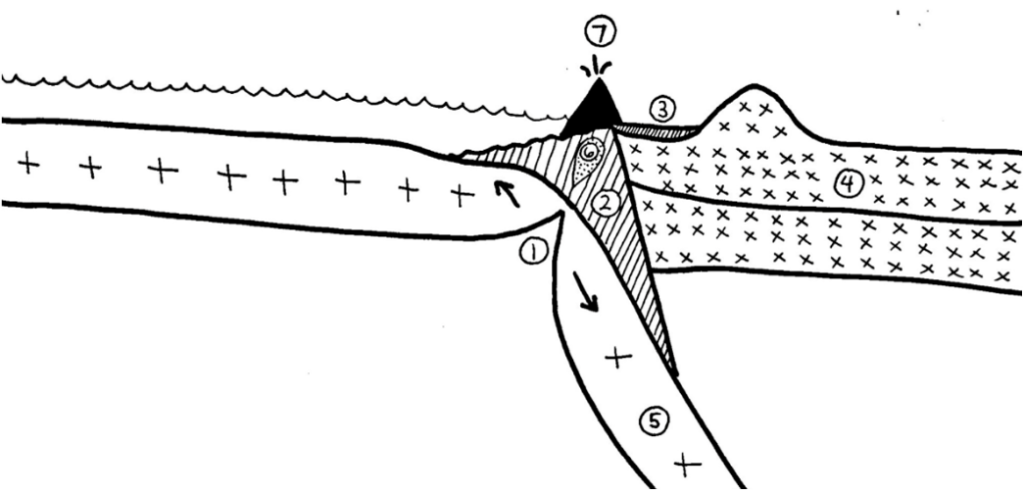

Eventually, the mid-ocean ridge (1) of the Farallon Plate neared the coastline and began to subduct as shown in the diagram below. Since the oceanic crust near the ridge was thin, magma rose at a shallow depth close to the subduction site (6). Thus, forming a line of volcanoes (7).

Key: 1= mid ocean ridge, 2= Franciscan Formation, 3= forearc basin, 4 = continental crust, 5 = oceanic crust, 6 = magma plume, 7 = volcano.

However, the rocks formed by these volcanoes are unique. As the magma rose, it mixed with a rock layer called the Franciscan Assemblage (2), a jumble of different rocks suspended in mud. If you were to walk around the other Nine Sisters, you would find bits of the Franciscan Formation scattered around their bases. This was moved there by the rise of ancient magma.

Over time, the mid-ocean ridge completely subducted, and volcanic activity ceased. Without a steady supply of magma, the volcanoes cooled and solidified into volcanic plugs. These plugs were buried underground and would not have been visible to anyone standing on the surface. Over millions of years, erosion from wind and water wore away the surrounding rock, exposing Morro Rock and the other Nine Sisters we see today.

Thinking Like a Geologist

Morro Bay and the Central Coast are rich with geologic wonders. So, the next time you’re hiking and come across a rocky outcrop, don’t just walk by. Take a moment to get up close, observe its texture, see how the light catches its crystals, and ask yourself, “How did this get here?”

If you are looking to see any of the Nine Sisters in person, download and explore this free map that is color-coded by accessibility to visitors and hikers:

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds.

- Subscribe to our seasonal newsletter: Between the Tides!

- We want to hear from you! Please take a few minutes to fill out this short survey about what type of events you’d like to see from the Estuary Program. We appreciate your input!