Guest post by Natalie Dupree

Dr. Emily Bockmon’s Ocean Chemistry Research Group

As an undergraduate chemistry student at Cal Poly, there were numerous research groups to consider joining. I chose to join Dr. Emily Bockmon’s research group, which is unique because it unites students from many disciplines under one common goal—to better understand the chemistry and impacts of climate change and ocean acidification on our Central Coast. Biologists, marine scientists, and chemists come together to collect data to support the scientific community and the community of Morro Bay to preserve and protect our bay and estuary.

This blog post serves as an insight into what a day in the life of a marine chemistry researcher looks like at Cal Poly, and to demonstrate the work we do for science and the community.

Sample Collection in Morro Bay

Sample collection materials

The sample collection day starts with gathering our materials from our lab at Cal Poly to bring to Morro Bay. We make sure we have clean bottles, our salinity probe, and a box containing rubber bands and clips, a sampling notebook, and other miscellaneous items. We also bring a special water collection bottle called a Niskin that has a stopper on each end and a spout near the bottom. ( Niskin is a brand name that we use to refer to the collection bottle the same way many people use the word Kleenex to refer to tissues.) If you’re interested in the details of how this equipment works, watch this video from Western University that shows a research team using a Niskin bottle to collect a marine water sample.

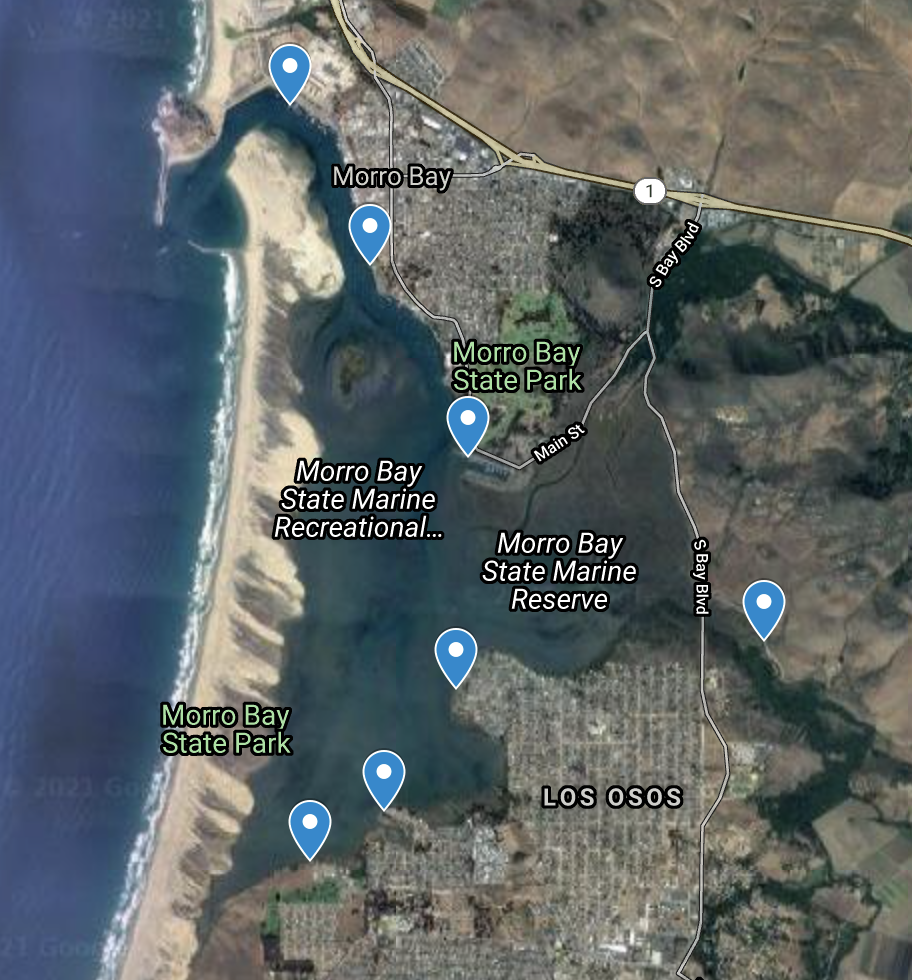

Sample collection locations

We collect samples at seven different sites around the bay. We usually schedule our sampling times during high tide to make sure that the water in the back bay is deep enough for us to collect water samples.

The water sample collection process

A group of three students collects samples each quarter. This helps collections go smoothly and allows for team building as we learn to work well together.

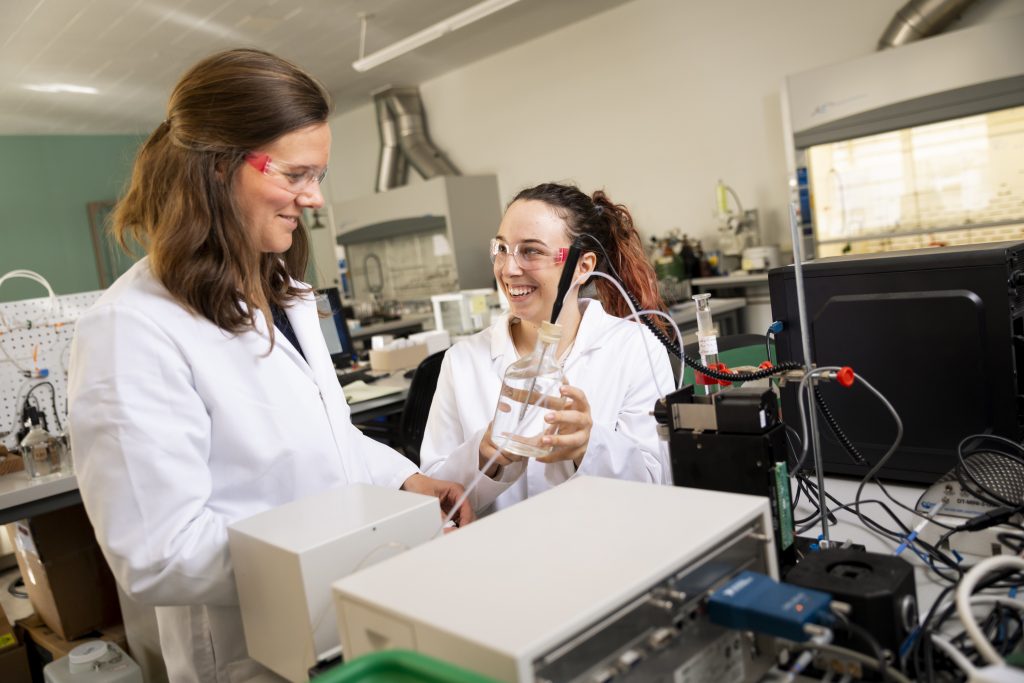

At the sample site, one person takes the Niskin and either wades into the water while holding it or lowers it into the water if wading isn’t possible to collect a water sample. Another student uses the salinity probe to measure the salinity, temperature, and oxygen saturation, which we record in our lab notebook.

Once the Niskin is full, we attach a tube to the spout of the Niskin and allow the water to drain out of it and fill a clean, empty bottle that we have labeled with the date and location of the collection site.

Preserving the sample for study in the lab

The water samples can contain plankton, microscopic organisms that use oxygen from the water in order to live. While biologists or marine scientists might study them, these tiny organisms can complicate our study of the water chemistry in the sample. In fact, any respirating life forms can completely alter the water sample’s chemistry by the time we get back to lab! To make sure this doesn’t happen, we “fix” the sample by adding chemicals to it that keep the levels of the water quality indicators at their original levels. Then, in order to make sure there’s no gas exchange between the water in the bottle and the air outside, we use greased glass stoppers, a clip, and a rubber band to make our bottles airtight.

After these steps, we pack up and head to our next collection site. By the end of collection process, wash of all our gear, and safely transport our bottles to the lab for analysis!

Testing ocean chemistry in the laboratory

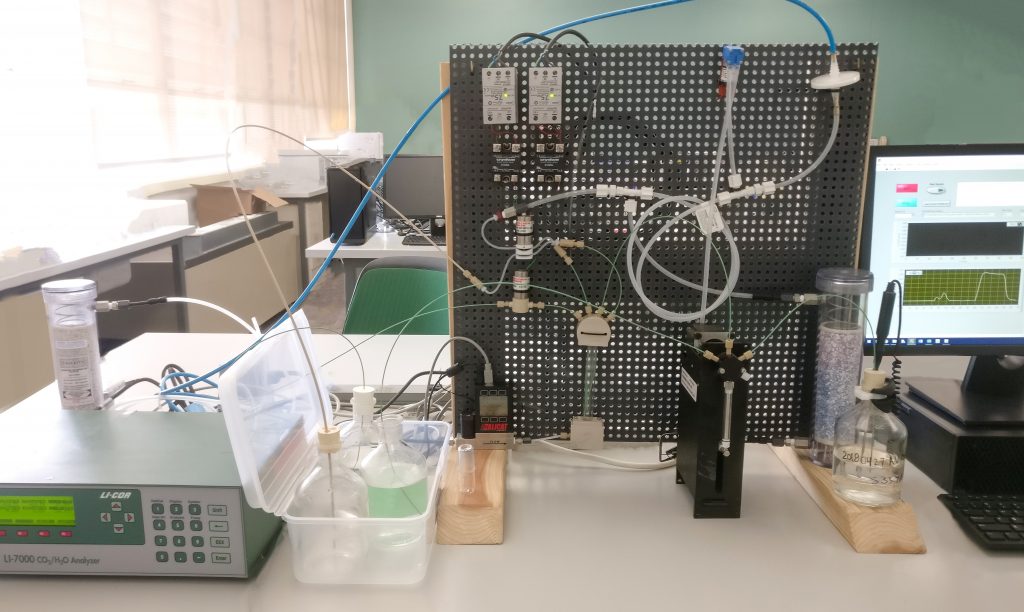

In our lab, we use three instruments to measure three components of ocean chemistry: pH, total dissolved carbon dioxide content (DIC), and alkalinity—Alkalinity, or the amount of salt in the water, is really important because it represents the , which helps guard the ocean against ocean acidification. Each student is trained to operate and understand one instrument, and we all work together to determine the chemistry of each bottle of seawater collected.

We run our samples in the order listed above to preserve their integrity. pH and DIC are most affected by gas exchange, and the second we open our bottles, some degree of gas exchange begins between the seawater in the bottle and the air in the lab. The student analyzing for pH checks the greased stopped seals of our sample bottle, notes their observations in their lab notebook, and then begins the analysis process.

After the first student finishes measuring pH, they recap the bottle and pass it to the second student who measures DIC.

After the second student finishes measuring DIC, the bottle passes to the third student who measures its alkalinity.

When they finish their data collection, they collect the water in a waste container.

Processing and checking our data

After a day of sample analysis, the researcher who operated each instrument processes the data collected and meets with Dr. Bockmon, our research professor, to certify it. To make sure our instruments are running properly and to calibrate our data, we use standard reference materials that have known concentrations. Our meetings with Dr. Bockmon are a great time to ask questions, and to solidify our understanding of the work we do and the data we’ve collected. We go over any problems we may have had during collection or processing, and make sure our data makes sense!

This work is important

One of the reasons I joined this research group is because of the significance our work holds. When we better understand the chemistry of our ocean and Morro Bay here on the Central Coast, we can better understand our environment. Our work to characterize the carbonate chemistry of Morro Bay may provide clues as to how the past loss of eelgrass continues to impact the health of the bay, and allows us to track changes in the bay’s chemistry as eelgrass restoration efforts continue.

For more information regarding our lab work, check out our website! https://bockmon.wixsite.com/oceancarbonlab

Guest post by Natalie Dupree

Originally from San Clemente, California, Natalie transferred to California Polytechnic State University–San Luis Obispo in fall of 2019 to complete her bachelor’s degree in chemistry. During her time at Cal Poly, Natalie participated in undergraduate research studying ocean chemistry with Dr. Emily Bockmon. Natalie also volunteered with the Morro Bay National Estuary Program involving eelgrass monitoring and pore water chemistry experimental design. In June 2021, Natalie graduated from Cal Poly and is currently pursuing a career as a chemist.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.