Sea Slugs on the Move: Bent on World Domination, or Opportunistic Travel Bums?

With the passing of the very low, very early morning tides of summer, tidepooling minds must reluctantly turn away from the outer edges of our coastline for a few months, until the autumn minus tides return in mid-October. And what better topic to occupy our Covid/smoke/asteroid/politics stressed minds than possible world domination by sea slugs?

I exaggerate, of course. We won’t be marching in lines and waving tiny nudibranch flags any time soon. But there has been a quiet movement of sea slug populations taking place, which humans are mostly unaware of though we have likely been its chief means of expansion.

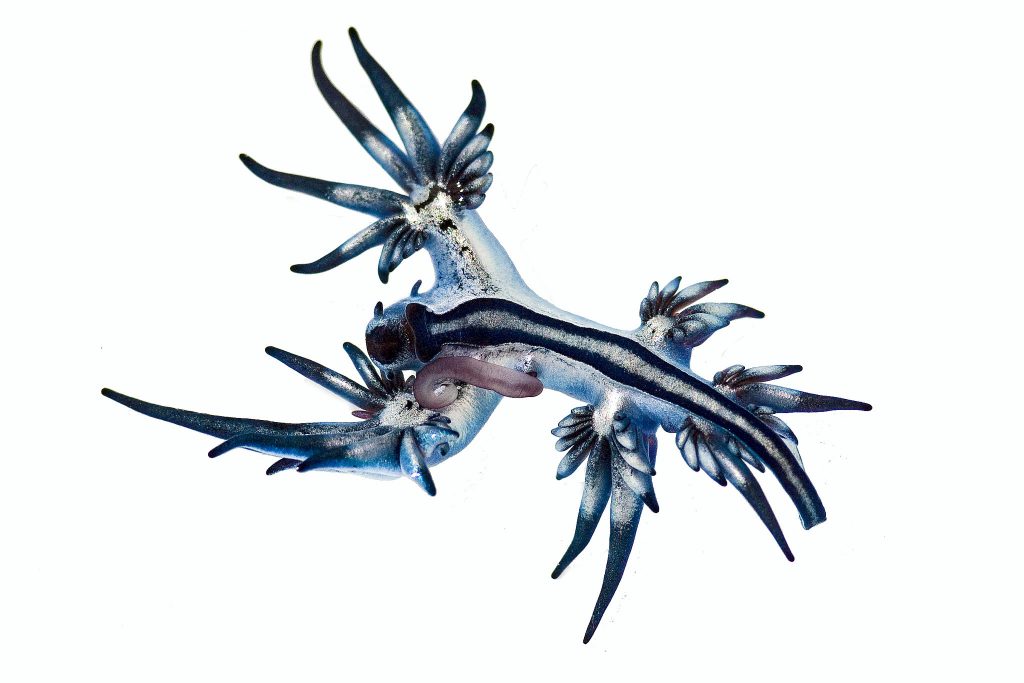

To back up for a second: what’s a nudibranch? Nudibranchs are gorgeous, shell-less marine molluscs commonly called sea slugs. Most are small: less than an inch long. Many display bright colors to warn predators that they will defend themselves with stinging cells sequestered in their cerata (digestive/respiratory organs on their backs) or in glands along the perimeter of their bodies.

There are over seventy described species of nudibranchs along the San Luis Obispo County coastline alone. The overwhelming majority have been traditionally described as ‘native’ species, meaning that they originated and live in the area without human intervention. However, scientists of both land and sea argue that subjective terms such as ‘native’ (which carries a positive connotation that implies the species should be protected) and ‘invasive’ (which doesn’t) are becoming blurred, if not altogether outdated, as climate change causes thousands of species to shift their traditional ranges in response to warming conditions.

Heating Things Up

Range shifts in response to warming seas certainly seem to be happening in the world of nudibranchs. Because nudibranchs generally lead short lives, and for most species their early development is spent as a microscopic veliger in the vast planktonic soup, swirling with wind, currents, and tides until they settle in a favorable location to live as adults, they are a potential early indicator of changing water conditions, notably temperature.

Two years ago, Dr. Jeffrey Goddard published a paper in the Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences documenting northern range shifts for 37 Eastern Pacific nudibranch species, including 21 from new northernmost localities, during the recent El Niño marine heat wave. Significantly, not a single species’ range was documented shifting southward.

“These numbers appear to be unprecedented in the historical record and point to global warming as a contributing factor, likely acting through a series of steps leading to increased poleward transport of coastal waters in the region, as well as elevated sea-surface temperatures,” Dr. Goddard writes.

On a side note: Your tidepooling photos matter! In addition to his own records and those of his colleagues, Dr. Goddard included data collected by citizen scientists (including a few from me, full disclosure) in his research. These photo observations, on iNaturalist.org and other sources, demonstrated the growing usefulness of simple citizen science projects to researchers. Any tidepooler’s submitted photos can become important data points, even if they don’t even know about the future research being conducted.

Drifters and Cruisers

A few nudibranch species are adapted to a pelagic lifestyle as adults, such as genus Glaucus, which lives and feeds on much larger Portuguese Man-o’-Wars and By-the-Wind Sailors (genus Velella). They drift with winds and currents, going wherever their prey goes.

Other world travellers such as Fiona pinnata live their adult lives primarily on floating objects like logs and kelp mats, munching on the goose barnacles, hydroids, and sponges that attach to these objects. F. pinnata is occasionally spotted in Morro Bay Harbor.

It also appears that nudibranchs are able to join humans on long transoceanic voyages as planktonic larvae. With the creation of port harbors, marinas and modern commercial shipping and recreational ocean travel, nudibranchs and many other sea creatures have been able to travel to areas outside their normal range. Large vessels take in quantities of ballast water in one location and discharge it in a different location. If the larvae survive the voyage in the ballast tanks, and settlement conditions are right, they may have an opportunity to establish new territory.

Whether or not they simply survive for a single season, or are able to breed and survive long-term in the new harbor environment, is an interesting question. About three years ago, in March of 2016, my daughter and I discovered a breeding group of seventeen Dendronotus orientalis nudibranchs in San Francisco Bay. This species had never been seen before anywhere in North America; they are normally found in Japan, and these individuals perhaps arrived in one of the many container ships that arrive each day in the bay. They had managed to find hydroids in the bay that were similar enough to their normal prey to be acceptable, and there were many egg masses already underway. But after that one instance, they have not been observed on the West Coast again.

This video shows Dendronotus orientalis nudibranchs in San Francisco Bay. Footage by Robin Agarwal. Shared via Flickr under a Creative Commons License.

Import, Export or ?

So which species is a ‘native’ and which is “introduced” or “invasive”? Perhaps these categorizations don’t matter. Sometimes even the scientists are stumped. One such origin mystery is the nudibranch Polycera hedgpethi, named for marine biologist and influential environmentalist Joel Hedgpeth. P. hegpethi was formally described from California in 1964, and is a commonly-seen species in Morro Bay Harbor, but it has been found in many port environments worldwide.

“Its present distribution around major seaports on the edge of the Indo-West Pacific suggests its present distribution is the result of shipping rather than natural causes,” wrote William Rudman in Sea Slug Forum in 1999.

Since then, observers have reported P. hedgpethi in Western Australia, South Africa, West Africa, Japan, Korea and the Mediterranean, primarily in ports. Where was the original home range of this species before it began its world takeover? In California, P. hedgpethi shares the same Bugula bryozoan diet as another Polycera species, the beautifully striped Polycera atra. (Also common in Morro Bay and other harbors, P. atra is notable for its variation in coloring: some individuals are primarily white, while others are primarily black.)

Purely anecdotally, I have never seen either Polycera cousin attack or displace the other in the prey-rich harbor environments they inhabit, so regardless of their origins, they seem to co-exist peacefully.

No Scuba AND No Low Tide, Still No Problem: Where to See a Nudibranch, Part 2: Dock Fouling

If you are fortunate enough to have access to a floating dock in a harbor or marina, you may be able to spot nudibranchs and other interesting dock fouling marine life at any time of the day, since this artificial habitat is not susceptible to the vagaries of tides. Public boat ramps, kayak docks, and other floating structures are often home to a surprising variety of sea slugs that prey on the sponges and bryozoans encrusting the sides and undersides of these structures.

WARNING: It is critically important that you ensure that you are not trespassing; many marinas and docks are private, and some boat owners do not take kindly to folks wandering around without permission. One bad actor can spoil it for everyone!

Once you indeed do have permission to take a look, lay down on the dock with your head hanging over the side and examine the sides of the dock. You’ll see anemones, algae, barnacles and other molluscs, small fish, and all sorts of interesting sea life. If it is nicely grungy, you may get lucky and see a nudibranch. (Insider tip: lay on a towel in case of gull poop.) Gently move aside algae as needed, but do not remove anything, since this habitat is surprisingly fragile. Pier pilings are also a good place to look, since nudibranchs can crawl up from below.

As with intertidal nudibranch hunting, GO SLOW. These beasts are small and it takes plenty of patience to find the tiny/beige/cryptic species. If you see one, leave it where it is, since it has somehow found food in this dock location.

Good luck!

Guest Author, Robin Agarwal

Lying flat on a bouncing floating dock underneath one of the biggest tourist-attraction piers in California, with my head and arms hanging over the side, I am frequently reminded of the kindness of fellow humans who think I’ve had a stroke or dropped my phone. No—just photographing sea slugs! I point, and show them a few photos on the back of my cheap underwater macro camera, and presto, another nudibranch enthusiast.

I was a tidepool kid who went astray and graduated with a liberal arts degree. In the last decade, I’ve returned to the tidepools and found a particular passion for photographing nudibranchs and other intertidal marine life. I’m co-editor of the California Sea Slugs Guide, and the Dock Fouling in California project on iNaturalist.org, where I have posted about 4,000 geotagged observations of nudibranchs, mostly along the Central California coast. Since I offer all my photos free to non-profit organizations (my way of thanking them for the work they do), you can find them all over the internet as well as Bay Nature magazine and NOAA National Marine Sanctuary informational signage. I’ve also been an enthusiastic contributor to a few scientific papers on nudibranchs, most recently Heterobranch Sea Slug Range Shifts in the Northeast Pacific Ocean Associated with the 2015-16 El Nino by Goddard et al. (2018).

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.