Paul Bump, Guest Author

Paul Bump is an explorer of the small and squishy. He completed his undergraduate degree at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 2016 in marine biology, and the spent two years working as a lab technician at the Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

As a fourth year PhD student in the Lowe Lab at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University in Monterey, California, Paul studies how an organism can build two wildly different bodies during its life while having access to the same genetic information. Through his research in strange, enigmatic, marine invertebrates, he hopes to unlock secrets around basic biological processes and provide novel perspectives to advance fundamental cell biology research.

Paul Bump on Researching Acorn Worms in Morro Bay: The Unknown Lives of the Small and Squishy

How does an embryo evolve from a single cell into the complex physical structures we see reflected in the diversity of animals on our planet? This process has captured biologists’ imagination for decades.However, the study of how some animals transform from one unique body structure to another very different one has been left on the sidelines. Animals with distinct adult and larval body structures are called indirect-developing species and represent a common developmental strategy, particularly in marine wildlife.

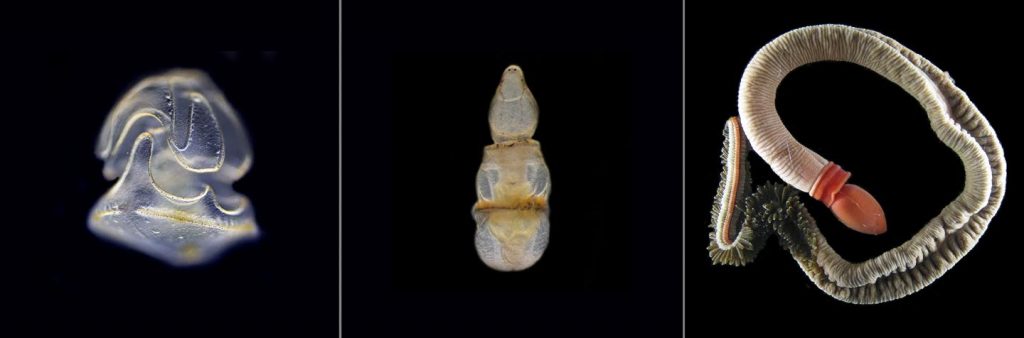

The main focus of my research is studying metamorphosis in the acorn worm, also called a hemichordate, Schizocardium californicum. This marine worm resides in the Morro Bay estuary, and is most often found in the Windy Cove area by the Morro Bay State Park Natural History Museum. The word, metamorphosis comes from the Greek meta, which means to change, and morphe” , which means to form. The process of metamorphosis occurs across many phyla, or biological categories, in the animal kingdom. Schizocardium californicum has a particularly intriguing metamorphosis, as it transforms from a small swimming planktonic balloon into a burrowing, muscular worm in twenty–four to forty–eight– hours.

Acorn worms are an evolutionarily important group of marine worms. They are more closely related to sea urchins and sea stars than earthworms. Work by my advisor Dr. Christopher Lowe and our lab at the Hopkins Marine Station has revealed surprising similarities between hemichordates and vertebrates.

Our lab first started working on Schizocardium a few years ago, when a previous graduate student in the lab, Paul Gonzalez, found a reference to a species of acorn worm living in Morro Bay in a 1994 marine animal survey. Through contacting the researchers from that decades-old paper, he was able to obtain the exact coordinates of the worm and locate our current field site. After that, we began to collect these worms, and bring them back to lab where they spawn, or reproduce. We grow the resulting animals from a single cell (the embryo) through its life cycle.

We have yet to find these specific worms anywhere else; we think that they may require very specific habitat conditions including sediment particle size (how fine or coarse the particles in the mud or sand are), wave exposure, etc. These specific requirements could make their distribution very patchy. Though these acorn worms may have difficulty finding a suitable place to live, these worms dig effortlessly through the thick, nutrient rich sediment, and their burrows often provide a home for other animals on the mudflat. When we are searching for them, we are often surprised to find a clam, a different species of worm, or even a fish living in an abandoned acorn worm burrow!

We are focused on understanding the mystery of how the genes expressed differ in the larval and juvenile stage of the worm’s development. During the larval stage, the worms are basically swimming heads. Only at metamorphosis does the rest of the animal’s genetic plan expand, and the larva transforms into a full body. These findings were published in a 2017 paper that you can read more about here.

My current work has been trying to undercover the cellular mechanisms behind these processes. I look at processes of cell birth, called proliferation, and cell death, called apoptosis, during the transition from the larval to the adult body. Do the cells of the larva become the cells of the adult? Or do larval-specific cells die and new cells proliferate to form the adult body plan? My research focuses on answering these questions. Though they may sound simple, these questions hide a whole world of complexity.

Our work can be intellectually and scientifically challenging. To add to the difficulty, we have to be able to find these elusive acorn worms to conduct our research. The worms seem to live just at the edge of the low tide mark, so unless we want to wade up to our waist in water, we have to time our searches carefully and a low tide is our best bet. Once we collect the worms, we have to transport them to our lab, and care for them at all life stages. Since little research has been done on these worms, our team has had to figure out what types of algae they eat and then how to grow that algae successfully in our lab.

The fact that this research could lead us to new perspectives on fundamental cell biology makes conducting our research well worth the unique challenges it presents. Someday, what we discover about acorn worms could inform scientists’ understanding of what makes stem cells similar across different groups of animals or how animals maintain the balance of cell being born and cells dying throughout their life cycle.

When you’re walking by Windy Cove, keep your eyes peeled for us. If you ever see us out on the mudflat collecting specimens, we’d love for you to say hello.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.