Yellow Blobs of Awesomeness: Sea Goddesses, Sea Lemons and That One with the Tentacles

Guest post by Robin Agarwal

Humans like sea slugs. They’re harmless to humans, but voracious predators if you’re a hydroid or a sponge. They come in a variety of cool shapes and sizes, and have fascinating life histories that allow one to throw around words like ‘nudi’ and ‘hermaphrodite’ with impunity in mixed company. But best of all, nudibranchs appeal mightily to humans’ attraction to pattern and color. We cannot resist taking a closer look at something bright and colorful as we explore an unfamiliar environment, such as a rocky shore at low tide.

Most of the bright yellow nudibranchs found along California’s Central Coast are various species of dorids: nudibranchs that have prominent external gills, often shaped like a flower or a ring of feathers, surrounding their anus. Yes, dorids poop from the middle of their respiratory system! In fact, the word “nudibranch” means “naked gills.” These fluffy gills are retractable when the animal is threatened, but are normally extended to uptake oxygen from seawater.

The backs of most of California’s yellow dorids are covered in papillae or tubercles, rounded bump-like projections that vary in size according to species.

Dorids feed primarily on live sponges (sorry Sponge Bob), slowly rasping away with razor sharp, tiny gastropod ‘teeth’ that are somewhat reminiscent of shark teeth, on a tongue called a radula. It’s a pretty unique feeding strategy, since sponges are not that easy to digest. This slow-motion predation is why the dorids’ bright colors start to make sense, too, since they are camouflaged next to their bright yellow, red, or pink sponge prey for hours or even days at a time.

The largest yellow dorid on the Central California Coast is Peltodoris nobilis (Sea Lemon), a magnificent beast that can grow to the size of a cell phone. Its common name derives from the bizzare fact that it smells a bit like citrus if handled too roughly. Its white gills, and the fussier fact that its black markings are only on its body and not its tubercles, distinguish it from the ubiquitous Doris montereyensis (Monterey Dorid), which has yellow gills and variable black markings on its tubercles only. These two species are commonly mistaken for each other, particularly in regions where both are called “Sea Lemon.”

Easiest to identify is Diaulula sandiegensis (San Diego Dorid), with its prominent, large, dark spots or rings on velvety yellow-beige papillae. Another yellow-beige dorid, Geitodoris heathi (Heath’s Dorid), has only a few scattered black markings. These often are concentrated just in front of the distinctive gills, which are white and emerge from an opening that appears flattened or oval in shape.

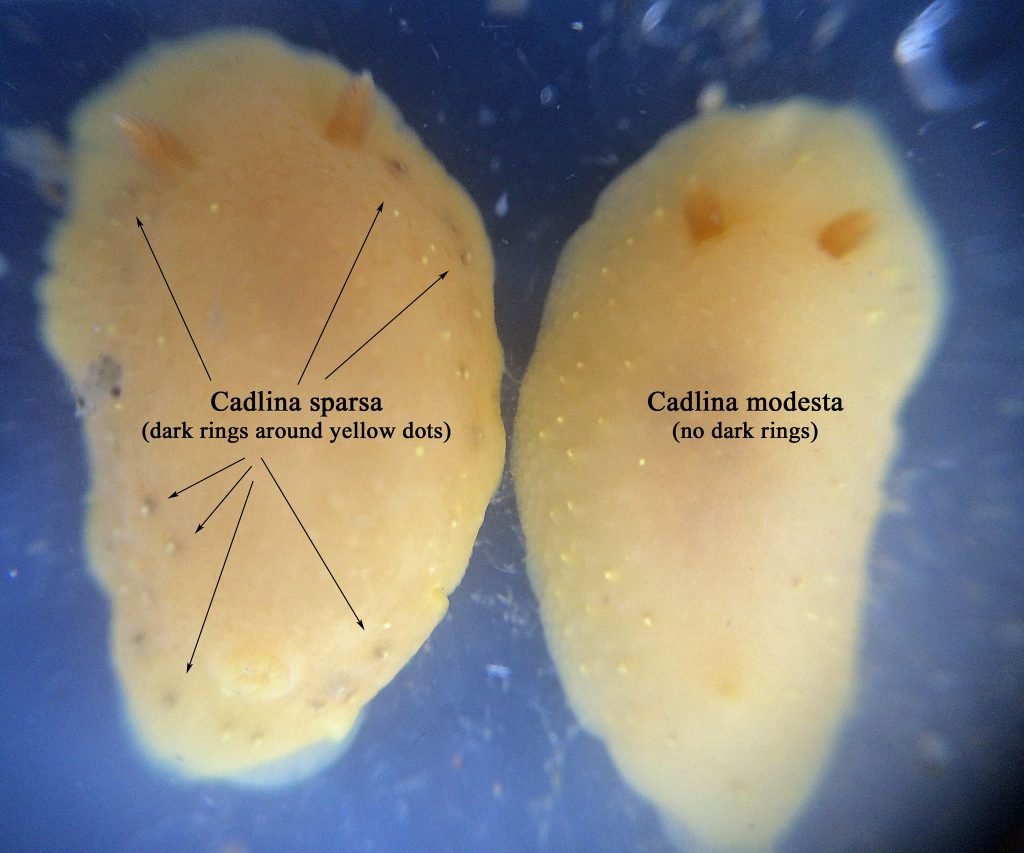

Cadlina modesta (Modest Cadlina) and Cadlina sparsa (Dark-spot Cadlina) are small yellow dorids most notable for their scattering of opaque mantle glands, often in a single row, that look like yellow spots around their mantle edge. Some or all of C. sparsa’s spots are ringed in dark pigment.

The elusive Hallaxa chani (Chan’s Dorid), a marvellously translucent yellow dorid with brown-tipped rhinophores and a scattering of small brown spots, was the first nudibranch discovery described by then-high school student and now nudibranch expert Terry Gosliner, who named it after his inspirational high school science teacher.

From a taxonomic point of view, one of the most controversial yellow dorids on the Central California Coast is the Doriopsillas, AKA Sea Goddesses. It is certainly outside the scope of this blog to do anything but present the briefest of overviews of the current thinking on these differences, but I’m including a brief mention, since it shows the fascinating issues that arise as new scientific tools become available.

A brief pause for a common name disclaimer—I have no idea which English-speaking naturalist took a look at these shell-less blobs and thought to themself, “Sea Goddess.” It seems a fanciful stretch, but a marvelously engaging one nonetheless.

“The Doriopsilla nudibranch species in California have been changing since the first species was described over 100 years ago,” says Maria Schaefer, a co-author for the description of the most commonly seen yellow-gilled Doriopsilla seen in California. “This is largely due to new tools becoming available and changes to the definition of a ‘species,’ in the same way that the definition of planets have been changing, e.g. Pluto. The most current Doriopsilla species definitions are determined predominantly by DNA differences, and nudibranchs within the Doriopsilla that can interbreed with these DNA differences are called “hybrids,” not different species. It will be interesting to see which tools will be used by future scientists (some may not even have been invented yet) to further elucidate the Doriopsilla species of California.”

While the key differences today are in the DNA, there are visual differences that correlate with the DNA differences. According to these scientists’ current Doriopsilla definitions, which are reflected in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), in the California Central Coast tidepools we have three species of Doriopsilla, distinguished by the color of their gills and the patterns of white spots on their back. Here’s how to tell the intertidal Doriopsilla species apart according to these definitions. The nudibranch’s background color (ranging from dark brown to bright yellow to almost white) does not matter.

- Doriopsilla albopunctata (White-spotted Sea Goddess) has white gills and a pattern of white spots on its back that resembles a galaxy: large and small spots on both the tips of the tubercles and on the back itself.

- Doriopsilla fulva (White-spotted Dorid) has white gills and white spots of more uniform size which are found on the tips of its tubercles only.

- Doriopsilla gemela (literally ‘The Twin,’ AKA Yellow-gilled Sea Goddess) has distinctive yellow gills. Its white spots are of variable sizes, somewhat like D. albopunctata, but do not extend as far down the edge of its mantle.

If you are an extraordinarily lucky tidepooler, like lottery-ticket lucky, there is a 0.0000001% chance you may encounter Doriopsilla spaldingi (Spalding’s Dorid – yellow gills, no white spots, and a stunningly beautiful opalescent blue border on its mantle) or Doriopsilla davebehrensi (Behrens’ Dorid – apparently indistinguishable from D. albopunctata except by DNA analysis), both subtidal species occasionally seen by divers.

Finally, if you are not confused enough already, there is another intertidal dorid, Baptodoris mimetica (Mimic Dorid), which looks very, very similar to Doriopsilla species with slightly more upright white gills and a scattering of white spots. However, this species has an identification giveaway: a pair of short oral tentacles on either side of its mouth (not present in Doriopsillas) that look like small vampire fangs.

Unexpected surprise!

Being colorful is probably a plus for warning away predators, sure, but it also makes us humans lean in and try to understand these marvelous little creatures. And with new tools at our disposal, we will slowly get closer to that understanding, whether we are in the lab or in the tidepools.

Guest Author, Robin Agarwal

Lying flat on a bouncing floating dock underneath one of the biggest tourist-attraction piers in California, with my head and arms hanging over the side, I am frequently reminded of the kindness of fellow humans who think I’ve had a stroke or dropped my phone. No—just photographing sea slugs! I point, and show them a few photos on the back of my cheap underwater macro camera, and presto, another nudibranch enthusiast.

I was a tidepool kid who went astray and graduated with a liberal arts degree. In the last decade, I’ve returned to the tidepools and found a particular passion for photographing nudibranchs and other intertidal marine life. I’m co-editor of the California Sea Slugs Guide, and the Dock Fouling in California project on iNaturalist.org, where I have posted about 4,000 geotagged observations of nudibranchs, mostly along the Central California coast. Since I offer all my photos free to non-profit organizations (my way of thanking them for the work they do), you can find them all over the internet as well as Bay Nature magazine and NOAA National Marine Sanctuary informational signage. I’ve also been an enthusiastic contributor to a few scientific papers on nudibranchs, most recently Heterobranch Sea Slug Range Shifts in the Northeast Pacific Ocean Associated with the 2015-16 El Nino by Goddard et al. (2018).

Works Cited

Gosliner T.M., Schaefer M.C., & Millen S.V. (1999) A new species of Doriopsilla (Nudibranchia: Dendrodorididae) from the Pacific Coast of North America, including a comparison with Doriopsilla albopunctata (Cooper, 1863). The Veliger 42(3): 201-210.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.