Summer is coming in hot! Iced tea, pool days, and movie nights are fast approaching. With all the excitement that comes with summer, you might not be thinking about the invention that allows our skin to survive the brutal rays of the sun—sunscreen.

Whether you are a fan of old-school white goop or spray-on, most sunscreens are made out of the same basic ingredients. The main difference lies in how the active ingredients work to keep you from burning. There are two types of sunscreen, chemical sunscreen and mineral sunscreen, which is also known as physical sunscreen.

Chemical sunscreen vs. mineral sunscreen

Chemical sunscreens contain chemicals that absorb the UV rays from the sun, rather than allowing your skin to take those rays in. Mineral sunscreens contain zinc oxide and/or titanium dioxide, both of which are white. This is why using mineral sunscreen usually leaves a white tint on your skin. Because sunlight bounces off of white pigments, mineral sunscreens act like a physical barrier, reflecting the sunlight away from your skin before your skin can absorb it.

The long history of sunscreen

What we now picture as sunscreen was invented in the 1970s. However, humans have a long history of trying to invent ointments to protect our skin from the sun’s rays. The earliest record of ointments being used for sun protection comes from the Egyptians, who used a combination of jasmine, lupine, and rice bran to protect their skin. Most of these ingredients are still being used for skin care to this day.

All around the world, ancient civilizations had their own versions of sunscreen. The Greeks used olive oil, some Native American tribes used Tsuga canadensis (also known as eastern hemlock), and in the Philippines they used a paste called orak or burak, which was made from water weeds, rice, and spices.

The development of modern sunscreen began in 1938, when a Swiss chemistry student named Franz Greiter suffered a sunburn while hiking. After that, he set out to invent an effective sunscreen. His first attempt, however, had only a Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of two.

In 1944, Benjamin Green, an airman and pharmacist from the United States, invented a substance called “red vet pet” also known as red veterinary petrolatum. He used this very greasy substance to protect himself and other soldiers from the sun during World War II. Soon after the war, he added cocoa butter and coconut oil to his recipe. He then began advertising it as a suntan lotion, now known as Coppertone, instead of a sun protection lotion.

Nothing really changed in the sunscreen industry until the 1970s, when better sunscreens were produced and the FDA began monitoring them for SPF levels. However, a lot of the ingredients introduced in the ‘70s are now known to cause damage to the skin and the environment. One of those ingredients is oxybenzone, which remains a key ingredient in most chemical sunscreens.

Oxybenzone causes coral reef bleaching

Oxybenzone acts as a genotoxicant to coral reefs, meaning that it damages the corals’ DNA. This damage ultimately kills the corals’ offspring, also known as planulae. The chemical does this by disrupting the skeletal endocrine of each planula, which essentially makes the planula encase itself in its own bone structure and die.

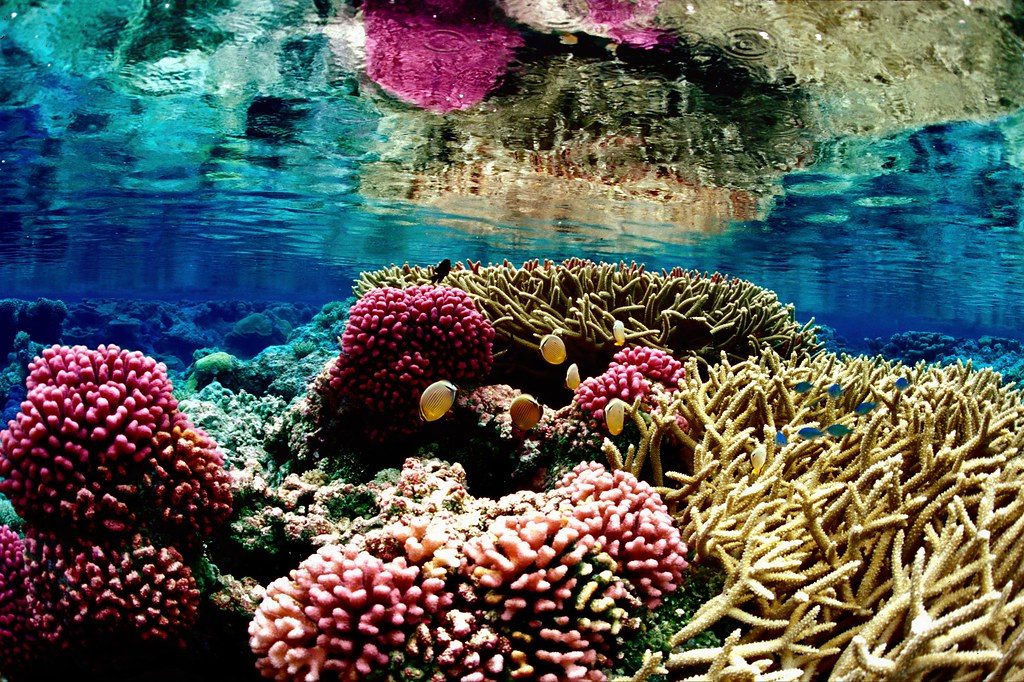

Beautiful unbleached coral reefs at Palmyra Atoll Wildlife Refuge Photo credit: Jim Maragos/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Beautiful unbleached coral reefs at Palmyra Atoll Wildlife Refuge Photo credit: Jim Maragos/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

This also affects the adult corals. The colors of the coral reefs come from a symbiotic relationship with algae, also known as zooxanthellae, which dwell inside the corals. The algae give the corals their luscious bright colors, provide oxygen, and act as a waste remover. Oxybenzone makes the water around the corals toxic, adding stress to their symbiotic partners. This stress awakens dormant viral infections in the algae, which leads to the coral to expel the algae. Without the algae, the corals turn white. This process is also known as bleaching.

Bleaching not only makes the corals less attractive, but it also makes them more susceptible to diseases, which ultimately leads to their death. To make matters worse, oxybenzone is a photo-toxicant, which means that exposing the chemical to light intensifies its adverse.

Because of its toxicity to coral reefs, Hawaii will be banning oxybenzone based sunscreen by 2021 in hopes of reducing coral- reef bleaching.

Oxybenzone affects human health, too

Oxybenzone isn’t just toxic to the environment, it can also harm humans. Research shows that when pregnant women are exposed to oxybenzone, it can lead to a birth defect called Hirshsprung’s disease (HSCR).This disease affects the development of nerve cells in the large intestine, which can make it difficult to pass stool. The condition often requires surgery to remove the affected area of the intestine.

Another problem with oxybenzone is that it reacts to chlorine, which is commonly used for pool sanitation and at water treatment plants to remove toxins from the water. Chlorine and oxybenzone react to form traces of chloroform, which has a higher genotoxicity than oxybenzone alone.

Oxybenzone has been found in urine and breast milk of people who use chemical sunscreen. Today, we do not fully understand the effects of oxybenzone on people. There isn’t much research on how much of the chemical we are ingesting, or how much of it ends up in our environment when we take a bath or shower after a day spent in the sun.

Still, its negative effects are starting to capture the world’s attention. Hawaii, Palau, and other locations across the world are banning oxybenzone as they recognize how this chemical affects their natural surroundings, especially their coral reefs.

Going on a hike? Don’t forget that even though you aren’t going near coral reefs that chemical sunscreens are still toxic! Grab your mineral sunscreen before you go! Photo credit: @ourallgoodadventure

These areas are now advertising the use of mineral sunscreens. Brands like All Good, Badger, Pacifica, and other mineral sunscreens, which are not toxic to humans and much less toxic to the environment, are slowly replacing chemical sunscreens. But, is mineral sunscreen really a good replacement for chemical sunscreen? We’ll answer that question next week.

Jump to a list of works cited.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have posts like this delivered to your inbox each week.

Help us protect and restore the Morro Bay estuary!

-

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

The Estuary Program is a 501(c)3 nonprofit. We depend on funding from grants and generous donors to continue our work. - Support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO. This locally owned and operated company donates 20% of proceeds from its Estuary clothing line and 100% of Estuary decal proceeds to the Estuary Program. Thank you, ESTERO!

- Purchase items from the the Estuary Program’s store on Zazzle. Zazzle prints and ships your items, and the Estuary Program receives 10% of the proceeds. Choose from mugs, hats, t-shirts, and even fanny packs (they’re back!) with our fun Estuary Octopus design, our classic Estuary Program logo, or our Mutts for the Bay logo.

- Donate to the Estuary Program today and support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

Thank you for helping our beautiful, bountiful, biodiverse bay!

Works cited

Aldahan, Adam S. “The History of Sunscreen.” JAMA Dermatology. December 01, 2015. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/article-abstract/2471534.

“CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21.” Accessdata.fda.gov. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?cfrpart=352&showfr=1.

Danovaro, Roberto, Lucia Bongiorni, Cinzia Corinaldesi, Donato Giovannelli, Elisabetta Damiani, Paola Astolfi, Lucedio Greci, and Antonio Pusceddu. “Sunscreens Cause Coral Bleaching by Promoting Viral Infections.” Environmental Health Perspectives116, no. 4 (2008): 441-47. doi:10.1289/ehp.10966.

Dinardo, Joseph C., and Craig A. Downs. “Dermatological and Environmental Toxicological Impact of the Sunscreen Ingredient Oxybenzone/benzophenone-3.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology17, no. 1 (2017): 15-19. doi:10.1111/jocd.12449.

Downs, C. A., Esti Kramarsky-Winter, Roee Segal, John Fauth, Sean Knutson, Omri Bronstein, Frederic R. Ciner, Rina Jeger, Yona Lichtenfeld, Cheryl M. Woodley, Paul Pennington, Kelli Cadenas, Ariel Kushmaro, and Yossi Loya. “Toxicopathological Effects of the Sunscreen UV Filter, Oxybenzone (Benzophenone-3), on Coral Planulae and Cultured Primary Cells and Its Environmental Contamination in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands.” Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology70, no. 2 (2015): 265-88. doi:10.1007/s00244-015-0227-7.

Ewg. “EWG’s 2019 Guide to Safer Sunscreens.” EWG. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.ewg.org/sunscreen/report/the-trouble-with-sunscreen-chemicals/.

Ewg. “EWG’s 2019 Guide to Safer Sunscreens.” EWG. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.ewg.org/sunscreen/report/nanoparticles-in-sunscreen/.

McMahon, Shannon, Shannon McMahon, and Shannon. “What Your Sunscreen Is Doing to the Environment.” SmarterTravel. April 22, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2019. https://www.smartertravel.com/what-sunscreen-does-to-the-environment/.

Penrod, Corinne. “Environmental Sunscreen Benefits.” Dermveda. May 02, 2019. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.dermveda.com/articles/environmental-impact-of-sunscreens.

Pierre-Louis, Kendra. “Hawaii’s Most Popular Coral Reefs Are in Big Trouble.” Popular Science. May 31, 2017. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.popsci.com/hawaii-coral-reefs-bleaching.

Schneider, Samantha L., and Henry W. Lim. “Review of Environmental Effects of Oxybenzone and Other Sunscreen Active Ingredients.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology80, no. 1 (2019): 266-71. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.033.

“Sunscreen: A History.” The New York Times. June 23, 2010. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/24/fashion/24skinside.html.

“The History of Sunscreen.” Yahoo! May 01, 2015. Accessed May 23, 2019. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/the-history-of-sunscreen-117797098013.html.