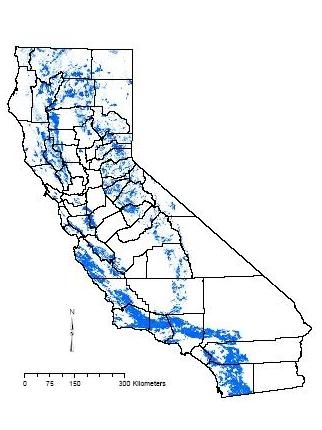

Covering almost nine percent of the state, chaparral is one of the most widespread plant communities in California. Not sure what a plant community is? Take a look at our introductory post to the Morro Bay Native Plant Series, an exploration of our watershed’s diverse native flora!

In the Morro Bay watershed, we see chaparral plant communities occurring in close association with the southern coastal scrub community and on higher, drier slopes. Since they are typically further inland from the immediate coast, chaparral plants experience greater temperature fluctuations (hotter summers and cooler winters) than coastal scrub plants, but the two communities often occur together in relatively similar soil types. The chaparral, or “hard chaparral” community consists of plants with woodier, denser, and often impenetrable branches compared to the southern coast scrub community, which is often referred to as “soft chaparral.”

Just inland from Black Hill, where we explored the southern coastal scrub plant community, sits Cerro Cabrillo. Here you will find mixed chaparral, in which multiple species of plants are equally dominant. Many of these species have sclerophyllous leaves. Sclerophyllous leaves are hard, small, and thick—all characteristics that reduce water loss and resist heat in a dry, warm environment.

Buckbrush (Ceanothus cuneatus) is a broad-leafed sclerophyllous shrub.

Chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum) is a needle-leafed sclerophyllous shrub.

Hollyleaf cherry (Prunus ilicifolia) is another broad-leafed sclerophyllous shrub.

Elderberry (Sambucus spp.) is another common chaparral plant.

Chaparral currant (Ribes malvaceum) displays striking pink flowers in the spring.

Morro manzanita (Arctostaphylos morroensis) is a federally endangered species that is endemic to the coastal areas of San Luis Obispo County (meaning it is found nowhere else in the world). This plant occurs in the maritime chaparral community, which can be found at the edge of the Elfin Forest and outside our watershed in Montana de Oro State Park.

The Chaparral and Coastal Scrub Mosaic

Because the southern coastal scrub community and the chaparral community often occur very close together (sometimes even mixing to form a mosaic), some plants are classified as members of both communities.

Sticky monkey flower (Diplacus aurantiacus) is an easily identifiable shrub with its paired orange blooms that some think resemble a monkey’s face. Press a leaf firmly between your fingers—it should slightly stick!

California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum) can be easily mistaken for chamise. You can differentiate between the two by noting each plant’s inflorescence, the technical term for the development and arrangement of flowers on a plant.

Fuchsia flowering gooseberry (Ribes speciosum) is easily identifiable by the dramatic spines at the base of its leaves and the bristles on its stems.

Many exclusively southern coastal scrub plants that we saw on Black Hill also occur on Cabrillo, such as toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) and California coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica). You will also see deerweed (Acmispon glaber) and black sage (Salvia mellifera) in full bloom!

Because it is extremely common throughout our entire watershed, look out for poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) on this hike. Remember—leaves of three, let it be!

To find out more about the native plants described in these blog posts, the Trees and Shrubs of California guidebook and the Calflora website are excellent sources of information. In our next Native Plants post, we will venture into an oak woodland community to learn about a characteristically central coast tree and its associated understory plants.

Subscribe to our weekly blog to have stories like these delivered to your inbox each week.

Donate to the Estuary Program to support our work in the field, the lab, and beyond.

You can also support us by purchasing estuary-themed gear from ESTERO or from our Estuary Program store!