Guest post by Jennifer Ruesink, a scientist and Professor at the University of Washington, Seattle.

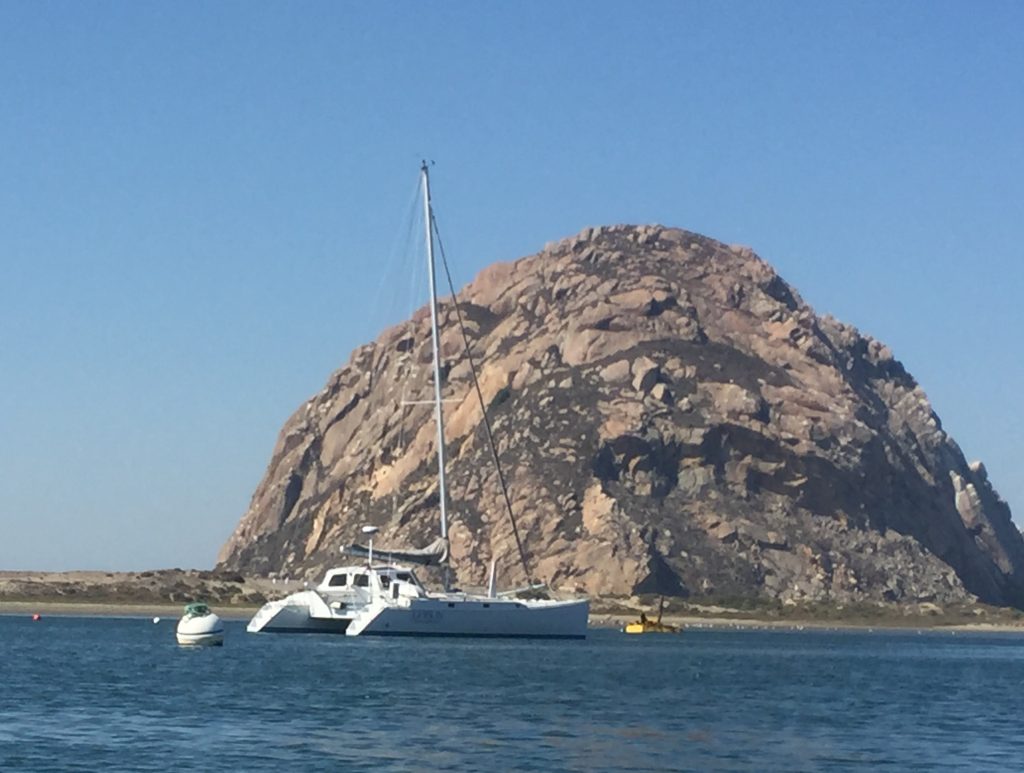

Jennifer Ruesink has been a faculty member at the University of Washington, Seattle, since 1999. Her expertise is in the ecology of estuarine ecosystems, especially structure-forming species such as seagrass and oysters. For her sabbatical in 2017-2018, she is visiting as many estuaries as possible along the Northeast Pacific coast, starting in Washington, as far south as Baja California, and finally around to Alaska before coming back down the coast. All these estuaries contain the same species of eelgrass, and many have commercial oyster culture. The twist of this biogeographic survey is it all being done aboard a 42 foot catamaran sailboat.

There’s been no shortage of evidence recently that the world is full of extreme events, from fires to floods. But it’s not just the weather that can be a sudden surprise. Sometimes we get to witness booms or busts of living creatures, and Morro Bay has had its share recently. Maybe you’ve looked down through shallow water over the mud and seen this?

Bulla gouldiana is a large gastropod, called a bubble snail. It has a thin, neatly-rolled, oblong shell, which its soft body can almost completely cover when it’s out crawling around. For decades, Bulla was so rare in Morro Bay that few people even recognized it. But over the past couple of years, these large snails (their shells can be 2 inches in diameter) became quite a phenomenon.

Oyster growers from the two local farms, Grassy Bar Oyster Company and Morro Bay Oyster Company, wondered if these snails were harming stock when they coated the oyster bags with their soft bodies oozing through the mesh. Scientists from Cal Poly and the Estuary Program found their eelgrass transplants festooned with yellow strands of egg cases.

Beachcombers picked up an unusual brown mottled shell, fragile and smooth. Serendipitously, when we were out measuring eelgrass on a low tide, just after dusk, we witnessed swarms of Bulla emerging from the sandy bottom and crawling to the canopy of the eelgrass bed – at least 80 snails visible in a square meter!

The Bulla phenomenon truly piqued the natural history interest of my traveling family science team, and we set out to learn what we could about how they came to be in Morro Bay, and what they might be doing here. We were sure glad that the Estuary Program staff brought up Bulla on the first day we visited to introduce ourselves, in response to our question of “what has changed in the bay?” Otherwise, we would have started with the challenge of simply determining the snail species name.

A quick check on the internet and in the scientific literature turned up pretty sparse information on Bulla gouldiana. It’s native to the California coast and reportedly can be abundant in bays. A few divers have taken pictures of it in pretty deep water. Larvae hatch out of those long yellow egg cases and float around with the plankton for a while. They feed on attached microalgae, which is frequently mistaken for brown scum in estuaries, but is really a productive milieu of microscopic photosynthesizing creatures.

During the day, Bulla hides out in the sediment, apparently traveling around by way of mucus tubes, but as we witnessed, they emerge to the surface at night. Most of the science done on the species has been behavioral.

Despite little in the way of quantitative ecological study, this information about the snail’s life cycle and diet helps us understand that Bulla are probably not consuming oysters through the mesh bags, and they are more likely to clean the epiphytes off of eelgrass than to eat the eelgrass itself.

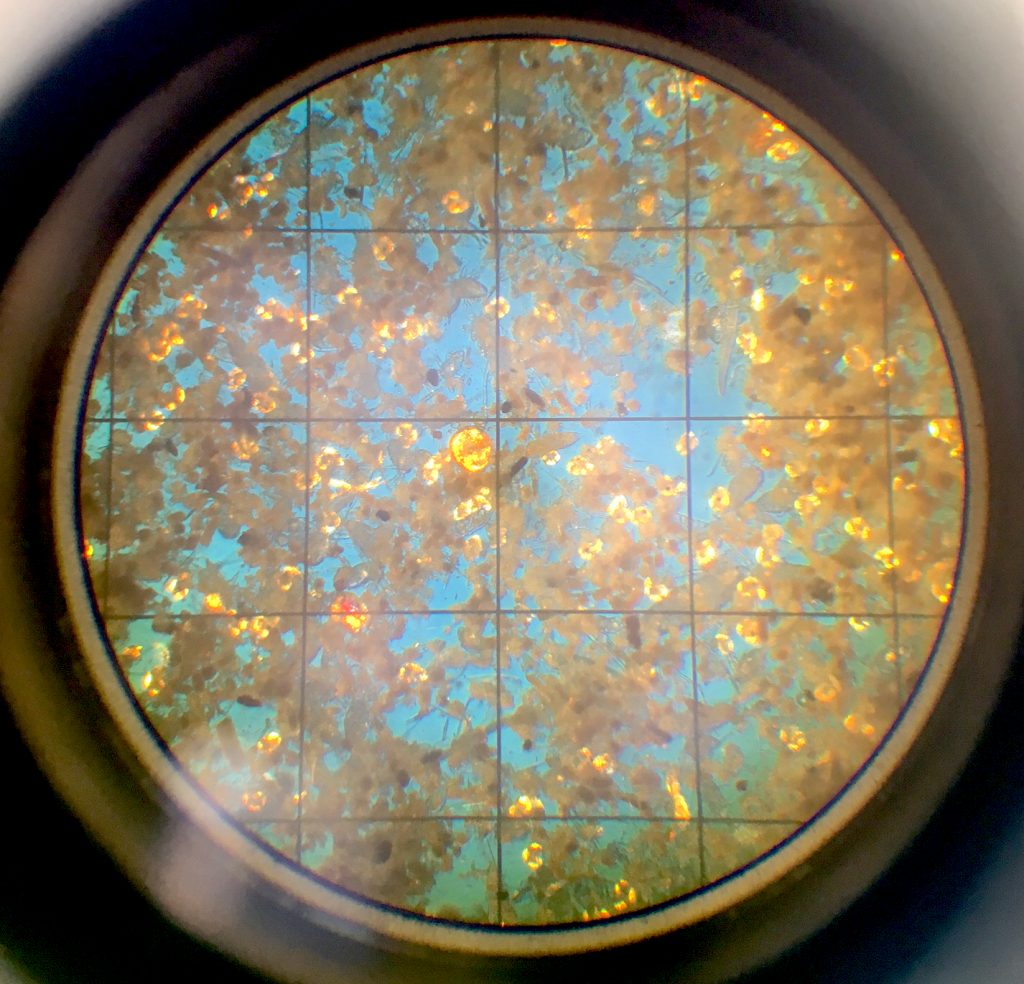

The science tools that we carry on our boat includes plankton nets and microscopes. We have a special inverted microscope (light from the top, view from the bottom) with polarized light, which spotlights larval mollusk shells as silver or gold glowing shapes, making them easy to distinguish from the vast array of other swimming creatures and drifting particles that get captured by a 60-micron net.

Everywhere we sampled in the bay, but especially in the back bay, tiny snail larvae were abundant. Imagine a microscopic snail shell, flying through the water on two round wings of transparent tissue, fringed by hairs (technically velar lobes with cilia). From the dark pigment spots on many of the larvae, we could tell that they were ready to settle out of the plankton. At metamorphosis, as the snails mature, they find a spot to shed those velar lobes and begin crawling around on a tiny snail foot.

We don’t know for sure that these snail larvae are Bulla. But Bulla are the most abundant snail around, and the timing is right, since the egg cases have been disappearing as larvae hatch out of them. These plankton samples help us understand that the Bulla in Morro Bay probably live their whole lives here—hatching, reproducing, and eventually dying in the bay.

This on-going spigot of larval delivery suggests that Bulla are here to stay, but that’s hard to say without information on how fast they grow or how long they live. For a while it seemed like there were just two phases present in Morro Bay – larvae and large adult. Then we started noticing smaller snails, just a half-inch long. Keep an eye out when you are watching birds or sea otters – have you seen anything eat Bulla? Or spit it out? You have an opportunity to help fill in a missing link, discovering whether Bulla is a tasty part of the larger food web in Morro Bay.

- Keep an eye out for future posts from Dr. Jennifer Reusink on eelgrass and oysters in Morro Bay.

- Please keep your distance while observing Bulla and any other wildlife. This will help keep you safe and avoid disturbing the animals.