National Estuaries Week runs through September 23 and celebrates the benefit we reap from our thriving coastal ecosystems. This has us thinking about how complex and special estuary ecosystems and the wildlife that thrives here are.

Estuaries are places of transition. The salty tides wash in and out over the mud flats, inundating the marsh and mixing with the freshwater influx from upland streams. The plants and animals that live in the estuary and the habitats that border its edges have special adaptations to survive these changes.

The time-lapse video above shows a complete twelve-hour tidal cycle in Morro Bay. (Video created for the Estuary Program by filmmaker Simo Nylander)

The California horn snail is one such creature. Horn snails are often seen in salt pans or shallow puddles left during low tide. In order to survive, these small sea snails close their shells off when the saltwater retreats and open up again during high tides. They feast on decaying plant matter brought in on the tides. They are perfectly adapted to the trials and the opportunities of life in the estuary.

Many different birds—both resident and migratory—use the estuary for food and refuge. They dip and glide above the water, sometimes wading and fishing or diving for food beneath the deeper water.

The snowy egret is a wading bird. In the picture below, it stands in a flooded patch of pickleweed with the pincer of a crab in its beak. Its long legs allowed it to wade into rising waters to catch this meal, which might have scuttled away or been elsewhere entirely at low tide.

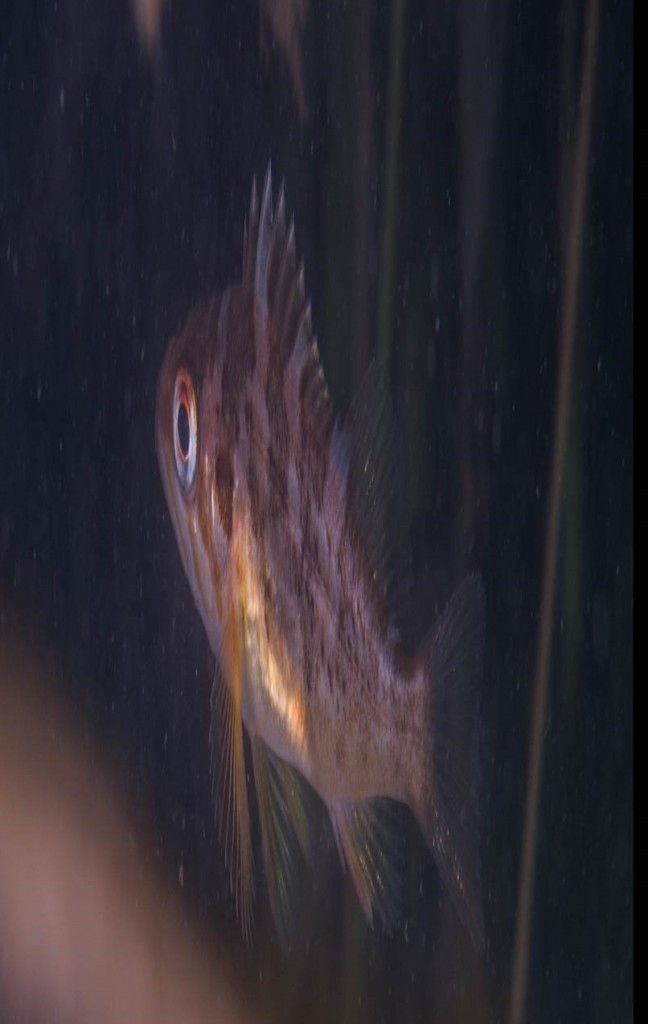

The estuary is also a place of transition and opportunity for young fish. Eelgrass beds provide a place for juvenile fish to hide from predators and find food while they’re growing. Some fish that use the estuary in this way, like the juvenile copper rockfish below (photographed with a GoPro), will eventually head out of the harbor mouth and into the ocean.

Morro Bay becomes even more beautiful when you consider all of these natural process-led transitions, complex interactions between wildlife and the environment, and the diversity of life going on beneath and all around the water’s edge.

Share your estuary stories, wonderings, and photographs online with the hashtag #EstuariesWeek.