Movies like Jaws and Sharknado can make sharks seem like mindless killing machines—even the dramatic music typically used to accompany footage of sharks has been shown to affect our perception of them. Despite their deadly pop culture image, the more scientists study sharks, the more they find that humans are not their intended prey. While species like great whites might “sample bite” humans, they rarely pursue people after that first bite. In fact, many shark attacks seem to be a case of mistaken identity, where the shark takes a surfer, paddler, or swimmer for a sea lion or a seal—their more typical prey.

Larger sharks, including the occasional great white, can be found in Estero Bay beyond the Morro Bay sandspit. The Morro Bay estuary, however, is home to three species of smaller sharks: the horn shark, the leopard shark, and the swell shark. These are slower-swimming sharks that prefer shallower waters and that often let their food come to them. Despite their different feeding styles, habitats, and sizes, all shark species play an important part in the food chain, helping to keep the ecosystem in balance.

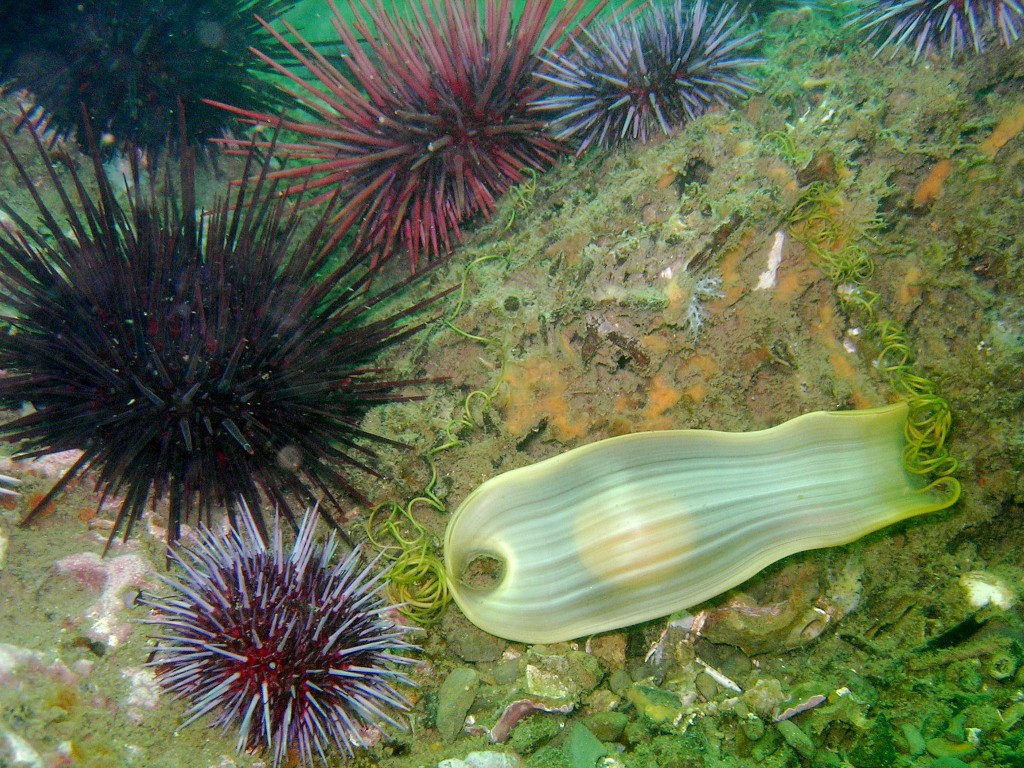

Today, we’ll focus on the swell shark. Swell sharks are not top predators—they eat crustaceans, small fish, and mollusks. They typically suck prey into their mouths when it comes close enough, instead of pursuing it actively. Swell sharks are also small enough to be prey for other sharks, seals, and sea lions.

In fact, this sedentary bottom-dwelling shark gets its name not from the ocean swell, as you might imagine, but from a unique defense mechanism. When threatened, it can take in water or air and swell up to three times its normal size. This makes the fish look larger and potentially more threatening. It also allows the fish to wedge itself between rocks, which may keep it from getting dragged off and eaten by a larger predator.

While swell sharks are not good to eat, they can be caught by anglers who catch and release them from local piers. They are most often found at night, when they feed. Because of the swell shark’s tendency to take in air and swell when removed from the water, it is best to put them back into the water as quickly and gently as possible to avoid injuring the animal. Some lore holds that swell sharks that are returned to the water after swelling give off a substance that keeps other fish away and spoils the fishing. This is a myth. Swell sharks will release the water or air they have taken in when they no longer feel threatened, but that is all.

Taking care to preserve these sharks is especially important because they take a long time to reach maturity—up to 20 years—and they release relatively few eggs. Any individual that dies before reproducing can be a big loss for the overall population.

Swell sharks that do live to reproduce do so by way of egg cases. The mother produces these tough-coated cases, colloquially dubbed mermaid’s purses, and anchors them in rocky algae-covered areas. The egg cases can be destroyed by marine snails that bore holes in them in order to consume the shark embryo. If they escape this fate, and if water conditions allow, the shark pup will hatch in nine to twelve months.

For more information on swell sharks and other shark species:

- Check out this fun swell shark anatomical poster from Squidtoons.

- Visit the Central Coast Aquarium in Avila Beach to see their shark tanks. Visit this weekend to hear from local “sharksperts” for Shark Week programming, both days at 11 a.m