A mysterious disease called Sea Star Wasting Disease Syndrome (SSWS) has been causing mass mortality of sea stars along much of the Pacific Coast from Baja California to the Gulf of Alaska. Twenty-two species of sea stars have been affected by it, making this a die-off event of the greatest magnitude, spread over the greatest geographic area to date.

Melissa Douglas, Associate Research Specialist at University of California, Santa Cruz, is an expert on the syndrome. She is concerned about the spread of the disease. As she says, “Past SSWS outbreaks were restricted to Southern CA and Baja Mexico. Now that the disease is being observed as far north as Anchorage, Alaska, it has become apparent that this is much more widespread than anyone would have imagined.”

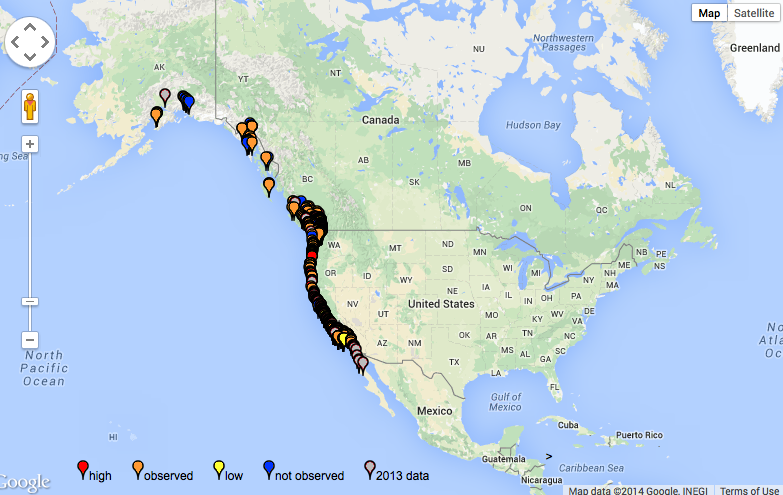

The Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe), who first discovered this wasting event in June 2013 in Washington, maintain a large-scale monitoring program that spans most of the west coast of North America. Having such a wide-reaching monitoring program has allowed MARINe to track the progression of the disease in an effort to determine what factors may be contributing to its spread.

This consortium of research groups monitors sea stars in the rocky intertidal zone at over 200 sites from Alaska to Mexico. As Melissa says, “Long-term monitoring programs such as MARINe are important because without them, there is no baseline to help determine the impact from something such as Sea Star Wasting Disease.”

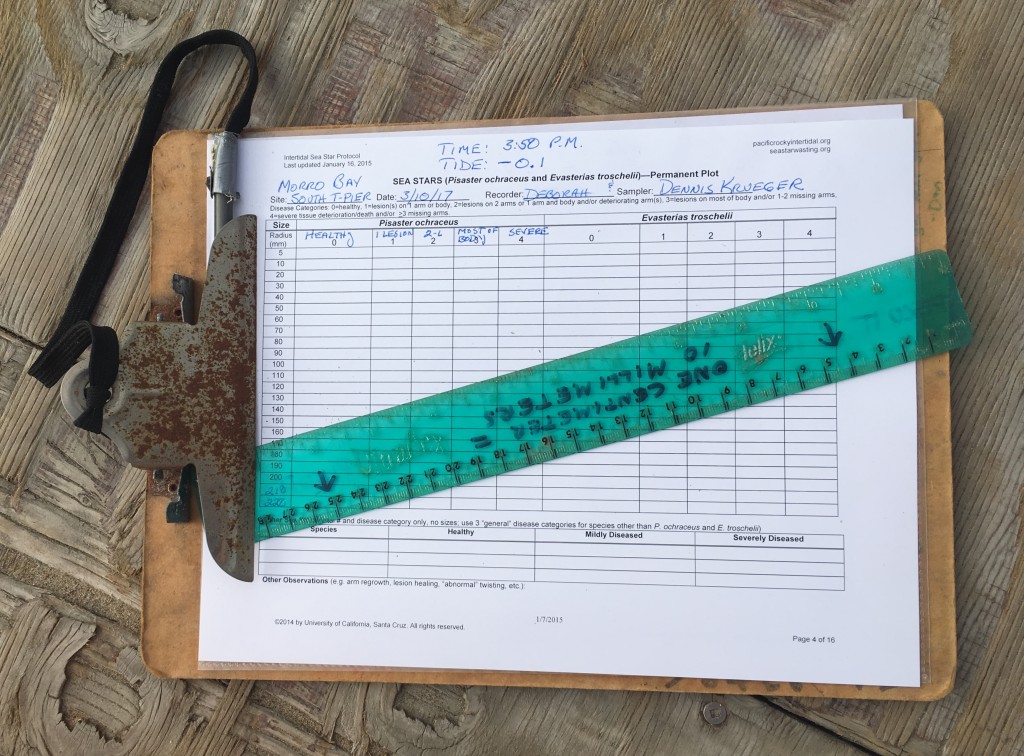

Citizen science groups trained by MARINe researchers have established permanent monitoring sites along the North American Pacific Coast to count, measure, and assess the conditions of sea stars in terms of the wasting syndrome. “Researchers can only be in so many places at a time,” Melissa says, “so tracking Sea Star Wasting Disease has only been made possible by citizen scientists getting involved. This has meant everything from someone casually sending us an email, to groups of citizens coming together to set up their own sea star monitoring plots.”

I had the privilege of monitoring a permanent site here in Morro Bay with Dennis Krueger, owner of Kayak Horizons. Dennis is a longtime volunteer for the Estuary Program and, after reading an article about Sea Star Wasting Disease, volunteered to establish a site here in the bay to monitor the sea stars. Melissa and an associate came down from UCSC to help him establish the site and start monitoring.

As a volunteer for the monitoring effort, Dennis kayaks out on the bay each month, during the lowest tides, to document sea stars and their conditions.

During our monitoring, we found one large, healthy adult ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus) attached to a piling.

Ochre stars are among the species of sea stars reported to experience high mortality rates due to Sea Star Wasting Disease. Ochre stars are keystone species, which are organisms that have a significant impact on other species in their ecosystem. The massive loss of these organisms could cause significant ecological consequences in their biological communities.

While change is often slow, Melissa and her team are already noticing some rocky intertidal sites drastically changing. “As a primary predator of mussels, ochre stars are largely responsible for the shape of the mussel beds. In some places where the population of ochre stars have plummeted due to SSWS, mussels are becoming more plentiful without this key predator and are expanding lower than we’ve ever seen before.”

A critical factor in evaluating these consequences is understanding how well these populations are reproducing, and if the disease also affects the juvenile sea stars.

Because the cause of the disease is not yet fully understood, MARINe is developing a spatial-temporal map (pictured earlier) to allow for the development of potential hypotheses concerning the causes of the disease.

I asked Melissa what we can do to help with research efforts.

“We encourage anyone—tide-poolers, students, surfers—to send their sea star observations to us via www.seastarwasting.org. Snap a photo or two if you see any sea stars, whether they look healthy or sick, and avoid touching sick looking sea stars because it may be possible to spread the disease to other sea stars.”

Despite the grim nature of this mortality event, Melissa sees a significant silver lining in the situation. She loves, “getting to see how many people care deeply about the ocean, and getting to see scientists and citizens come together to try and solve a problem.”

Although the future of the disease is unclear, Dennis and I were happy to have found a healthy sea star in our beautiful bay. As monitoring continues, we hope to see more.

To learn more about Sea Star Wasting Syndrome, visit the MARINe database here.

See Catie’s recent post on eelgrass replanting efforts in Morro Bay.