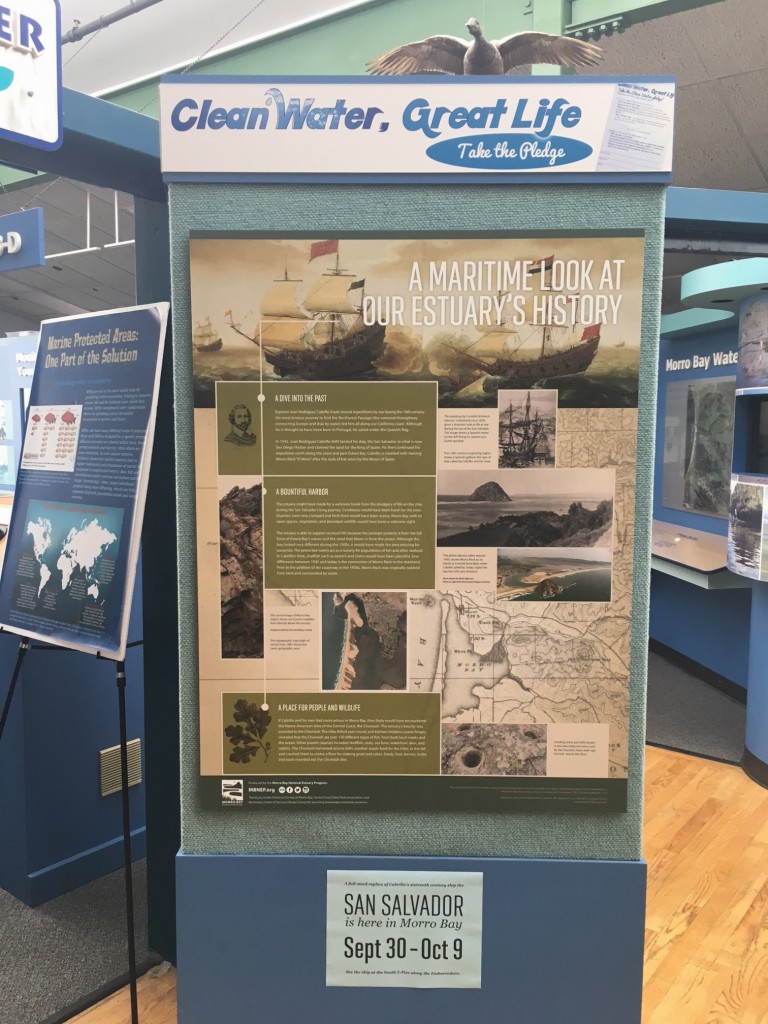

Morro Bay History is Alive

On September 29, 2016, a replica of explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo’s ship, the San Salvador, docked in Morro Bay. Cabrillo made several voyages by sea during the 1500s. His most famous journey to find the Northwest Passage led him along the California coast. In 1542, he landed his ship, the San Salvador, in what is now San Diego Harbor and claimed the land for the King of Spain. He then continued his expedition north along the coast and past Estero Bay. Cabrillo is credited with naming Morro Rock “El Moro” after the style of hat worn by the Moors of Spain.

A Bountiful Harbor

Though there is no record of Cabrillo entering Morro Bay, the estuary might have given the crew a welcome break from the drudgery of life on the ship during the San Salvador’s long journey. Conditions would have been harsh. Quarters were very cramped and fresh food would have been scarce. Morro Bay, with its open spaces, vegetation, and abundant wildlife would likely have been a welcome sight.

The estuary is able to support so much life because the sandspit protects it from the full force of Estero Bay’s waves and the wind that blows in from the ocean. The protected waters act as a nursery for populations of fish and other seafood. In Cabrillo’s time, shellfish, such as oysters and clams, would have been plentiful.

A Place for People and Wildlife

If Cabrillo and his men had come ashore in Morro Bay, they likely would have encountered the Chumash, a Native American tribe of the Central Coast. The estuary’s bounty was essential to the Chumash. The tribe fished year-round, and their kitchen middens (waste heaps) reveal that the Chumash ate over 150 different types of fish, from both local creeks and the ocean. Some of their other protein sources included shellfish, seals, sea lions, waterfowl, deer, and rabbits. The Chumash harvested acorns—another staple food—in the fall and then crushed them to create a flour for making gruel and cakes. Seeds, fruit, berries, bulbs, and roots rounded out the Chumash diet.

A Changing Rock and Bay

Morro Rock and Morro Bay have changed quite a bit since Cabrillo’s time. The Rock once sat as a towering island, with water flowing into and out of the estuary from the north and south sides. Boats could enter the bay from both directions, but it was known as a treacherous harbor.

Beginning in the 1800s, Morro Rock was quarried. This activity continued until 1968, when Morro Rock was declared a historical landmark. In 1910, quarried rock was accidentally dumped into the bay, closing the north channel and resulting in less-severe tidal currents in the harbor. In 1933, a more structured closure and connection of the Rock to shore was built. The causeway was improved in the 1940s to allow both vehicle and pedestrian access, creating what is today’s Harbor Walk.

Today, Morro Rock is about two-thirds of its original size, with more than 1,200,000 tons of granite taken from the east and west sides of the formation. The quarried rock helped build both Morro Bay and neighboring Avila Beach’s barriers from the open ocean.

Even with all these changes, the sandspit still protects Morro Bay from the full force of the ocean as it did before the closure, allowing the estuary to remain a refuge for juvenile fish, a wide variety of migrating birds, and other animal life.

Visit and Learn

If you would like to get a glimpse, or a even a tour, of Cabrillo’s ship and try to imagine Morro Bay and the Rock they would have looked so many centuries ago, you can. The San Salvador is docked in Morro Bay now through October 9.

To learn more about how Morro Bay has changed since Cabrillo sailed California’s coastline, visit our Nature Center and see our new display boards.

Subscribe to get the Estuary Program’s blog delivered to your inbox each week!

Donate to help the Estuary Program protect and restore Morro Bay.

Many thanks to the Historical Society of Morro Bay and the Central Coast State Parks Association for providing historical information and reference materials.