Last year, we wrote a post about the Sea Star Wasting Syndrome, a disease that was causing mass mortality of sea stars along the Pacific Coast from Baja California to the Gulf of Alaska. The syndrome is a general description of symptoms found in affected sea stars. Typically, lesions appear on the surface of the stars followed by decay surrounding the lesions, leading to fragmentation of the sea star’s body and eventual death. According to biological oceanographer and microbial ecologist Ian Hewson from Cornell University, this disease is by far the largest marine disease event ever seen.

Hewson’s lab at Cornell University has been focusing on determining the cause of the disease. Initially, the disease was thought to have been linked to a type of virus, a densovirus (SSaDV). However, further study has concluded that if a densovirus is responsible, it is only in the case of sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides). For ochre stars and other hard-hit sea stars found along the Pacific Coast, there is still much work to be done before this mysterious disease is fully understood. As Hewson says, “Disease among stars is likely caused by multiple factors, not just one.”

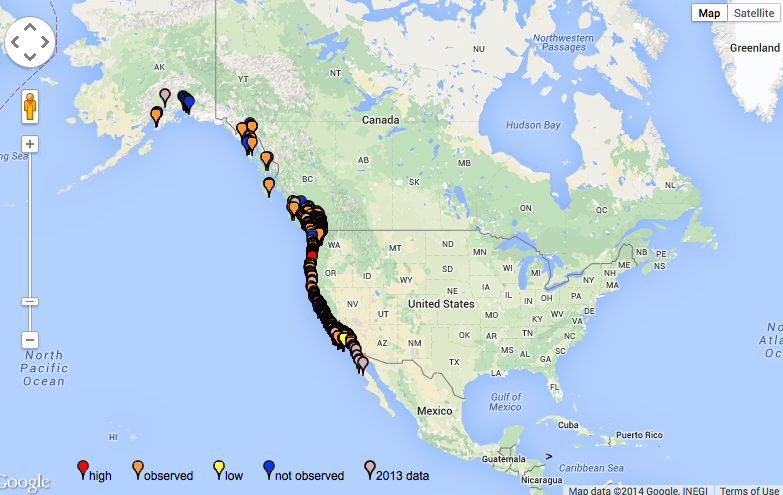

In our last post, we spoke with Associate Research Specialist Melissa Douglas from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her group, the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe) monitors over 200 sites from Alaska to Mexico to track the progression of the disease over time. They examine the effects of the disease on various sea star populations, and how the decline in sea stars impacts the greater community as a whole.

For this post, we spoke with Melissa Miner, UC Santa Cruz Researcher and colleague of Melissa Douglas, to see what updates she could share. Melissa regularly monitors sites from Oregon to Alaska, and has found that the disease is still persisting, but at very low levels. It is not yet known why the disease has lessened in most places.

“It’s unfortunate that we’ve lost so many sea stars,” Melissa Miner says, “but in some ways it allows us to test this idea that ochre stars are drivers of community structure.” Because sea stars eat many other organisms, Melissa and MARINe have already noticed some changes in the biological communities in which the sea star populations have declined.

The predicted expansion of mussel beds, for example, has occurred in some places, but more research is required to determine that the expansion is due to the decline in sea stars. A new collaborative project between UC Santa Cruz, UC Santa Barbara, and Oregon State University is looking at these factors that result in community change. Their findings will be released in a year or so.

Much of the sea star wasting disease data is generated by the public through MARINe’s citizen science program. I joined Dennis Krueger of Kayak Horizons again to monitor Morro Bay’s site at the south T-pier. We didn’t find any sea stars at the south T-pier; however, we found eight ochre stars under the north T-pier and countless bat stars. Bat stars (Patiria miniata) are affected by the syndrome but to a much lesser degree than ochre stars and other species. Since we do not know the cause of the disease, it is hard to speculate why some species might be more affected than others.

“The citizen science effort behind the sea star wasting syndrome helps forge a better connection between what MARINe is doing with their long term monitoring and the general public,” Melissa says. Although the sea star wasting syndrome is a complex and not yet understood occurrence, the involvement of the community is a new and positive outcome of this event.

You can be a citizen scientist too!

Send photos of any sea stars you encounter (including the location and species) to MARINe’s data webform. Your information is greatly valued in this large-scale and long-term study.

Join us for a free evening of engaging science talks!

Morro Bay Science Explorations: Local Fish and Fisheries

Thursday, June 14, 6:00 p.m. at San Luis Obispo Botanical Gardens

You’ll hear three presentations from local experts

- Local Watershed Stewards Program (WSP) Members will give an overview of their program and the exciting projects they’ve undertaken to help anadromous fish in our area.

- Grant T. Waltz, Cal Poly Researcher, will explore the effects of a decade of groundfish protections through local MPAs.

- Sean Lema, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at Cal Poly, will discuss a new approach to measuring the growth of groundfish in the wild, which has applications to fisheries management. Learn about his research and the Lema Lab.

We’ll gather at the SLO Botanical Garden’s Oak Glen Pavilion. Doors open at 6, talks start at 6:15, and light refreshments will be served. You can find more details on our Events Page or on our Facebook account. The event is free and open to the public, and we would love to see you there!